When institutions are made out to seem god given and impossible to change, it is also more difficult to imagine other kinds of institutions. A concrete example of this is an observation made by several longtime philosophy teachers that it is very difficult to get upper secondary school students to imagine alternative or utopian societies. Only a decade ago, the exercise yielded a multitude of imaginative and innovative ideas.

Both in political theory and popular discourse, utopian societies have recently been relegated to the sidelines. At times, they have even been pronounced dead.

Not later than the 1990s, the so-called Popperian critique of utopianism became a mainstream line of thinking. Popperian critique of utopianism refers to a work by Karl Popper called The poverty of historicism, published in 1957. Popper critiques utopias as “social blueprints”, whose execution ultimately leads to coercion (“utopian social engineering”). In the post- Cold War climate, people started to be wary of grand social utopias, viewing them as “totalitarian”, and the self-understanding of politics was focused on governance.

If politics is not guided by a vision of a qualitatively better society, it regresses to technocracy, where the democratic space is narrowed significantly.

Despite all this, the ability to think utopistically is needed to preserve the meaning of politics: it needs vision, hopes and imaginings that transcend current “realities”. If politics is not guided by a vision of a qualitatively better society, it regresses to technocracy, where the democratic space is narrowed significantly.

The phenomenon needs researching from two angles, firstly from the perspective of contemporary criticism. What does the weakness of our utopias tell us about our era? Secondly, it needs to be researched as a question of critical methodology: does social research have a role in strengthening utopian thinking? Next, I will look at how the state of utopias can be observed from the perspective of contemporary criticism. In the Conclusions-section, I will return to the question of the role of research.

Collective and private desire for something better

Striving for something better and dissatisfaction with the present are both a part of humanity. Sociologist Ruth Levitas has called this “a desire for a better way of being”. Even though all functional human beings have this desire, it can be channeled in wildly varying ways. Societal, social and psychological structures may either support or limit different forms of alternative imagination or action.

Roughly speaking, the existence of “something better” may be realized through two distinct means.

Collective desire for something better is about aiming to imagine and realize better societal structures and modes of co-operation. This precise aim is what utopias are tools for achieving. The significance of utopias can’t be reduced to how much they have been applied or whether they can be applied. Aside from functioning as “blueprints”, they are above all tools of criticism and “roadmaps”. In other words, utopia helps in perceiving the problematic aspects of the world as it exists and in mapping out a desired direction of change.

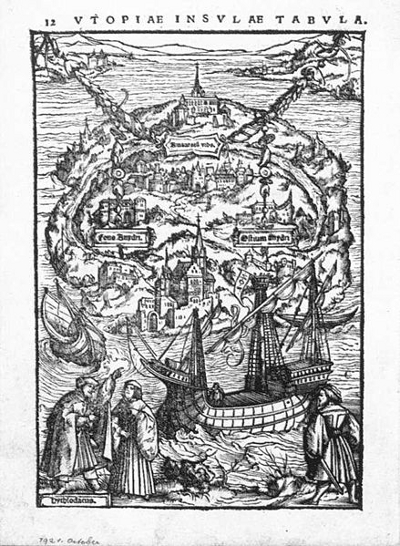

Utopias can be clearly fictitious: the most famous example might be Thomas More’s book Utopia (1989 [1516]). On the other hand, they can be “real utopias” (Wright 2010). Real utopias describe, in one way or another, aims that open up new prospects and whose realization might be conceivable. Basic income could be viewed as a typical modern-day example of this.

While utopias have been declared dead, individual “values” and individualistic lifestyle politics are emphasized in popular political discussion.

Private desire for something better, on the other hand, refers to reacting to the unsatisfying aspects of reality by attempting to distance oneself from them on a personal level. In this case, the person in question is still motivated by desire for a better way of being but does not ask how social reality could function differently or what kind of co-operative action should be taken to realize the desired change. The most typical example of a private desire for better is the effort to organize one’s life so as to make it less busy by “fleeing the rat race”.

The private channeling of the desire for a better way of being can be viewed as a dominant contemporary phenomenon. While utopias have been declared dead, individual “values” and individualistic lifestyle politics are emphasized in popular political discussion.

Zeitgeist: Private escape projects

The privatization of the desire for a better way of being refers exactly to the emphasis placed on individual life projects. These efforts are commonly described as “downshifting” or “fleeing the rat race”.

Of course, human beings have a right to make efforts towards improving their own lives – there’s nothing bad about downshifting as such. It is, however, remarkable that these efforts for a better life seem to not leave any room for social utopias. On the contrary, they often rely on the types of structures that make the mapping out and realization of utopias more difficult.

I performed a review of Finnish news related to downshifting. Without exception, they consisted of lifestyle stories, lacking in any vision for social change. Two main themes or manners of description could be discerned from the rhetoric of the downshifters. The first one is control of one’s own life (“there is no one to tell me I need to be somewhere at a certain time and telling me how to do my job”), (“the goal of downshifting is to focus on things that matter to you”). The second theme is search for balance (“Is it possible to achieve that kind of wonderful balance, where the amount of work is satisfactory, while the work is meaningful and there is enough time left for other aspects of life as well?”).

These stories are often underpinned by a very secure, even privileged economic position (“I am able to live on dividend income. It should be noted that living on government benefits is not downshifting”).

It is, then, worth asking, whether the all-pervasive technocratization of politics could partially be a consequence of the fact that imagining a better existence is focused on private projects like this, given that these projects might even be reliant on re-enforcing the current economic order.

Zeitgeist: imagining backwards in time

Another noteworthy contemporary phenomenon is the reversal of the time perspective of imagination.

The natural direction of imagining social utopias is forwards: utopia is a future that could become real. A future perspective may be very concrete: for example, the unfinished welfare state has been a type of future-oriented “real utopia” in its own time. Then again, the current “welfare state fatigue” can also be connected to the loss of utopian future perspective: in theory, the governance of the welfare state works just as well as before, but the weakening of a sense of an optimistic, utopian vision for the future erodes its support.

The weakening of the future perspective does not just imply rising pessimism. Sociologist Zygmunt Bauman (2015) wrote about the subject Retropia, which ended up being his last work. According to Bauman, modern times are characterized by the tendency to imagine pasts instead of futures. In other words, past-oriented (nostalgic) imagination is replacing future-oriented (utopian) imagination.

In a reality dominated by the imagining of pasts, political imagination draws from various fictitious or idealized conditions in the past. Politics starts to become dominated by fantasies of “return”. It is remarkable how nowadays the dominant (and competing) alternatives to neoliberalism and technocratic governance are the return to equality (welfare state) and the return to a nation state. Neither of the options represents future-oriented thinking.

The disappearance of imaginative capabilities and their strengthening

Despite all this, utopias aren’t destined to disappear, just as their existence is not automatic. The ability to imagine alternative societies and modes of co-operation has to be cultivated. Therefore, it is pertinent to ask what kind of factors strengthen and what kind of factors weaken our collective imaginative aptitude.

Political scientists have often paid attention to the narrowing of political space. The phenomenon has aptly been called “disciplinary neoliberalism” or “new constitutionalism” (f. ex. Gill 1998). Several of the political changes cemented after the Cold War were problematic not only in terms of their content, but also because they started to resemble constitutions in stature. For example, trade agreements or EU treaties are extremely difficult to change by means of democratic politics.

However, as far as the effects of the “lock-in” of politics go, less attention has been paid to the narrowing of imaginative abilities as a result of the narrowing of political space. When institutions are made out to seem god given and impossible to change, it is also more difficult to imagine other kinds of institutions. A concrete example of this is an observation made by several longtime philosophy teachers that it is very difficult to get upper secondary school students to imagine alternative or utopian societies. Only a decade ago, the exercise yielded a multitude of imaginative and innovative ideas.

Social imagination can be based on artistic creativity, such as in classic utopian literature, where the authors often wrote about fictitious “islands” that existed outside the real world. Thomas More, Tommaso Campanella and Francis Bacon, among others, depicted places of this kind, existing “somewhere far away”. What was noteworthy was not just the organization of the societies but also the skills and attitudes of their citizens. Even though stories of this type belong largely to the realm of fiction, these fictitious worlds can actually be highly important as tools of imagination and critique.

Building concrete, small-scale alternatives and learning from the successes and failures of these projects trains imaginative capabilities as well. The development of micro-level practices (such as urban civic activism projects and co-ops) can help in perceiving the possibilities and the characteristics of larger scale, alternative forms of organization.

Conclusions

Navigating towards a better society requires the ability to imagine societies that function differently. Imagined reality is a tool that makes the possibility of a change in the existing reality visible, along with the need for the change. In this light, utopians can be conceived of as a compass of sorts for a community to use (Wright 2010). On a similar note, if the ability to imagine alternative realities weakens, politics is reduced to short-sighted fine-tuning of details and “alternative action” becomes privatized.

Indeed, it is worth asking how individualistic expressions of a desire for a better way of being could be modeled into societal efforts. The privatization of a desire for a better way of being is not only a pessimistic zeitgeist, but also a challenge to look for unitary narratives, experiences and efforts from privately experienced efforts. Private escape projects are rooted in the same need as utopian thinking but are channeled in a different way in the prevalent atmosphere of our society.

Social scientists may play a significant role in this. The social scientist can attempt carefully to “verbalize” sources of discontent so that they resonate with a larger group of people. They can also offer tools for developing social imagination. After all, the purpose of social sciences is to perceive general and structural qualities in phenomena that appear to be singular and random on the surface.

However, the effort also requires breaking down methodological barriers. A kinship between social science, pedagogy and arts could prove very valuable in this effort.

Translation by Jarkko Hagelberg. The translator is a Master’s-level student of Multilingual Communication and Translation Studies at Tampere University. The translation was produced as part of a project course in English Translation.

References

Bauman, Z. (2015). Retropia. Cambridge: Polity.

Gill, S. (1998). New constitutionalism, democratisation and global political economy’, Pacifica review: Peace, security and global change 10(1), pp. 23–38.

Levitas, R. (2010). The concept of utopia. Oxford: Peter Lang.

More, T. (1989). Utopia. Cambridge: Cambridge University press. Latin original 1516.Translated into English by Robert M. Adams.

Popper, K. (1957). The poverty of historicism. Lontoo: Routledge.

Wright, E.O. (2010). Envisioning real utopias. Lontoo: Verso.

Translation by Jarkko Hagelberg. The translator is a Master’s-level student of Multilingual Communication and Translation Studies at Tampere University. The translation was produced as part of a project course in English Translation.