SARS-COVID-19 has significantly slowed down economies and stalled life in many cities across the globe. This hits very badly millions of taxi-drivers, among them Uber and other platform drivers whose social rights and security are least protected. The platforms react to the crisis in different ways.

Pandemic hit hard both global and local economies

The SARS-COVID-19 epidemic started at the times of reported emerging trade barriers, escalating geopolitical tensions. The World Economic Forum (2019) describes how weakened international collaboration damages collective will to tackle global risks. In December 2019 the growing epidemic caused closure of many Chinese factories and created difficulties for corporations, which rely on Chinese industrial capabilities. In early 2020 the pandemic has hit the international travel, small and big businesses across the globe. And by the middle of March the grim economic projections foresee a global Corona recession.

One of the first measures to tackle the spread of the virus was restriction of people’s mobility. Governments across the world started to screen or ban travelling and travellers first from specific and then more broadly. National borders have been closed and in epidemic areas these measures moved into more severe restrictions of mobility between regions and in restricted areas. Social distancing has resulted in governments and businesses asking people to stay at home, to work remotely when possible, and avoid social contacts. Shopping malls, concert halls, and theatres are closed. Trade fairs, conferences and entertainment events have been cancelled. To enforce nation-wide quarantines some countries (for instance, Slovakia and Czech Republic) banned passenger transportation by taxi platforms allowing only grocery delivery.

The politics and reactions by governments for control of COVID-19 pandemic were brought up by Salla Atkins and Meri Koivusalo. Here we focus on implications of the COVID-19 pandemic on platform economy workers, zoom on taxi-drivers. We analyze also how platform providers have reacted to the epidemic.

Taxi sector and pandemic wave

The COVID-19 pandemic with a dramatic decrease in social activities and consumption has an immediate impact on most business sectors, including transportation of people. Taxi companies estimate 80-90 % decline in numbers of taxi rides within a week between 13-20 March. Finland’s Taxi Association officially “Suomen Taksiliitto” demands local and state responsibility for income compensation for taxi entrepreneurs, who suffer from the suddenly ended school transport as one major aspect of the reduced mobility. Media reported on 31 March that the government of Finland had introduced a flat sum of 2000 euros benefit scheme for those solo-entrepreneurs and freelancers, whose business is substantially weakened by the Corona crisis. There is funding for 50 000 persons. The implementation of the scheme at the municipality level is under process. Furthermore, the government of Finland will extend unemployment benefits temporarily available for the entrepreneurs, although the final details about the scheme are to be decided. Both these schemes help entrepreneur-workers, like Uber drivers, to cope with their severe business losses in this unusual situation.

How does the COVID-19 epidemic affect the most vulnerable part of the workforce, the platform workers, some of whom work in the taxi-sector? Taxi drivers earnings are dependent on freedom of mobility and on established rhythms of urban life: people travel to work, go out to eat, attend concerts and sports events.

How does the COVID-19 epidemic affect the most vulnerable part of the workforce, the platform workers, some of whom work in the taxi-sector? Taxi drivers earnings are dependent on freedom of mobility and on established rhythms of urban life: people travel to work, go out to eat, attend concerts and sports events.

The digital applications have multiplied the use of taxi in 7-million-resident St. Petersburg, where the COVID-19 now stalls the urban life. Taxi-drivers we interviewed there as part of the Academy of Finland Uberisation: Rights, Regulation and Redistribution research project said that their earnings during St.Petersburg International Economic Forum in 2019 allowed them to enjoy troubleless summer vacation. Similarly in Helsinki, many newly started Uber drivers were busy during 2019 summer months.

Now, in St.Petersburg, the International Economic Forum 2020 is cancelled and even more severely EURO 2020 football tournament is postponed 12 months to summer 2021 due to a coronavirus outbreak. St. Petersburg has over 25 000 active taxi licenses and tens of thousands of taxi drivers are now affected by the closure policies announced on March 18, 2020 with no compensation of lost earnings for self-employed drivers. Local government discusses the possibility of subsidizing loan interests for small businesses and automatic extension of work permits for immigrant workers. The government of the Russian Federation presented its own COVID-19 economic crisis plan that included: state regulation of prices on food and essentials, subsidies interest rates for business loans, compensation of losses to transportation and tourism companies. Furthermore, Russian president Putin proposed emergency measures that included mortgage, debt, and tax holidays, increasing unemployment benefits, bankruptcy protection and tax reliefs for small businesses.

Emerging protection for platform economy workers

The ride-hailing platforms (simplified as “taxi platforms”) rely on the vulnerable work of those whom they call “driver partners” (Isaac 2014; Srnicek 2016; Zwick 2018). Despite of having extensive control over their work times, work intensity, client base, the prices, and how the work has to be carried out, there is only a handful of cases, when platforms have been obliged to treat these “partners” as employees (for instance, the gig economy law in California, or the decision by the Cour de Cassation in France).

Being an employee gives a driver a more protected position in relation to health care and social security, although the impact of the difference between these two employment status are widely dependent on welfare state context. Majority of Uber drivers in Finland are entrepreneurs with a clear division of responsibilities between drivers, Uber and public services.

Russia is a more complicated context. Yandex.Taxi is the biggest ride-hailing platform in the Russian taxi industry. A driver can work with it either through a myriad of big and small taxi companies (they are often called “taxi parks”) or directly an entrepreneur/self-employed partner. We can raise concerns on a majority of Yandex.Taxi drivers in Russia who seem to work in the grey zone of law. Many drivers have no contract neither with a taxi company, nor with a ride-hailing platform company. Only a tiny fraction of drivers work as entrepreneurs or self-employed partners. In case sickness, taxi driver’s obligatory health insurance covers only a basic level of medical treatment guaranteed by the state and municipalities. Furthermore, Russian taxi drivers have obligatory daily health check-up and vehicle control which resonates from an earlier time, when all drivers were employees. Before the COVID-19 epidemic these control maneuvers were applied in a mixed way within Russian taxi sector.

Before the COVID-19 epidemic hit hard, the platform taxi companies – being pressured by workers – were developing ways to protect drivers from evident insecurities attached to their worker position. Some platforms like Uber and Yandex.Taxi offered drivers guaranteed minimum earnings based on the number of rides: drivers can choose to make 10, 20, or 30 rides and get guaranteed earnings. These policies are based on the assumption that urban mobility is not disrupted and there are persistently large numbers of customers who take rides in the city. This type of security mechanisms on earnings are particularly vulnerable to diminishing customer flow, and does not necessarily help drivers in today’s crisis situation. Furthermore, during the unfolding epidemic the Yandex.Taxi reduced the guaranteed payments to drivers in Russia.

Platforms respond to health risks

The COVID-19 poses new health risks to the taxi industry. A taxi driver and a customer are not only sharing the ride, they are also sharing the risk of getting disease. Media has reported on an Uber driver operating in Long Island, New York, while he was waiting for his coronavirus test results. Once Uber was alerted to the positive test, the driver’s access to the Uber application was revoked. These kinds of reckless drivers are a fundamental threat to Uber’s, or any other application taxi company’s, reputation. If any fatalities result from this kind of situation, it may result in a costly court case in the US.

Obviously, there are many drivers world-wide who have become infected with COVID-19 and are unable to be on-line and driving. To minimise the risks for drivers and customers the Uber and other platform taxi companies are now developing their own policies for regulating work during emergencies.

To minimise the risks for drivers and customers the Uber and other platform taxi companies are now developing their own policies for regulating work during emergencies.

Most new policies go beyond earlier emergency measures of suspended surged prices, subsidized free rides or temporarily shutting down their services. Still, there is remarkable variation in policy response to COVID-19 epidemic between companies. The policies range from recommendations to ventilate the cars (Yandex.Taxi in Russia) to temporary suspending drivers’ and customers accounts (Uber in the US and Mexico), or mobilizing drivers for relief work (DIDI in Wuhan, China). In early February 2020, news broke that Uber suspended 240 accounts in Mexico to prevent the possible spread of the coronavirus. Similarly in London, Uber driver’s account was suspended after delivering a coronavirus patient to a hospital. Uber did not publish any numbers of how many drivers were suspended world wide.

In our view, the Russian government seemed first to downplay the threat of COVID-19 epidemic and many businesses reflected on this policy in their operations.

In the beginning of April there were no confirmed reports about suspended accounts of Yandex.Taxi drivers or customers in Russia. There the ride-hailing platform informed drivers that they will be fined by the transportation authority if they do not have disinfection sprays available and don’t wear medical masks.

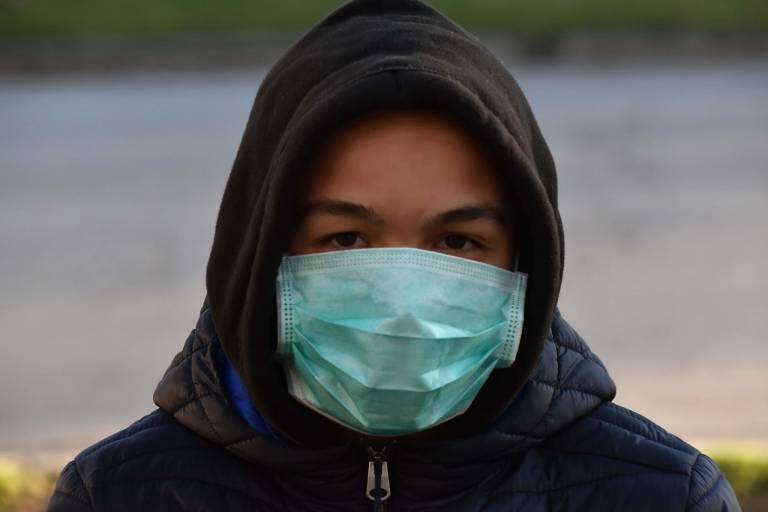

Picture 1: Uber introduced sick leave compensations for drivers. Source, 17.03.2020.

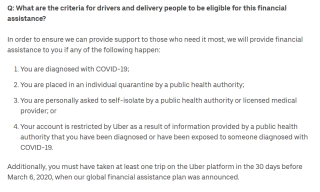

In March some of the largest ride-hailing platforms like Uber, Didi, and Lyft introduced compensations for drivers who were infected or were forced to stop working due to quarantine or self-isolation. Uber and Lyft promised drivers to compensate for sick leave for 14 days if they are eligible (Picture 1). Lyft’s compensation policy is based on driver’s average earnings during the last four weeks. Uber’s sick pay is counted from the driver’s average daily earnings during the last 6 months. Other companies Bolt, Gett, Yandex.Taxi took no responsibility at the beginning: “drivers are independent service providers who use our platform”, Bolt, March 12, 2020 (Picture 2).

Picture 2: Bolt takes no responsibility. Source, 17.03.2020.

In our view, the Russian government seemed first to downplay the threat of COVID-19 epidemic and many businesses reflected on this policy in their operations. In the beginning of March, the Yandex.Taxi told drivers about some basic prevention measures (Picture 3), then it offered its drivers free medical masks and disinfectants at Moscow Sheremetyevo airport, also the 40 automated health diagnostic units were said to operate free of charge for drivers.

Picture 3: Yandex.Taxi tells about prevention in its 3.03.2020 post. Source, 17.03.2020

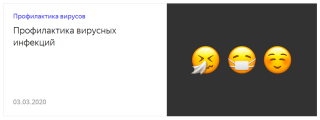

In the end of March Yandex updated its Coronavirus-response policy and announced a program for financial support of divers: infected or quarantined drivers can get a compensation for 14 days that amounts to 50% of daily earnings based on rides from the past 6 months (Picture 4). Drivers are obliged to present evidence to support their claim: a statement from hospital and a document from local government authority.

Picture 4: Yandex.Taxi announced compensations for drivers on 23.03.2020 Source, 24.03.2020

In Finland, the Social Insurance Institution, KELA, has a particular sickness allowance on account of an infectious disease, which are paid if you have been given an order of isolation, quarantine or enforced absence from work because of an infectious disease. An infection disease control doctor’s certificate presented, this scheme gives full compensation of a salary. But as Uber drivers in Finland are solo-entrepreneurs their benefit are calculated based on their individual social insurance payments. As all Uber drivers started after August 2018, when the new taxi act legalized Uber’s activity, their benefits are small compared to ones of the full time salary workers. This is why Uber’s own sick pay plays important role in securing drivers’ incomes.

High demand for food delivery

In response to COVID-19 epidemic the governments and cities across the globe have adopted quarantine and self-isolation policies. This hits the transportation sector hard. But the effect may be quite different in comparison to the food delivery service sector. The food delivery services; dominated by the platform companies, like DoorDash, UberEats, Wolt, Foodora, Deliveroo may even see the surge of workload as customers stay at home and avoid going out to eat. This has been an opportunity for companies such as Uber to incentivise drivers to move from ride hailing to food delivery (UberEats). In reaction to COVID-19 the delivery company Wolt introduced ”no-contact-delivery”. There was a short surge in delivery app download in the US, while grocery delivery apps download numbers demonstrated a more consistent growth.

The COVID-19 epidemic is a test of trust between customers on one side and companies, employees and contractors on the other. The masses avoiding the infection should be confirmed by the hygienic procedures of the service process. Food delivery is certainly needed more than before among people who spend more time in their homes and avoid contact with others, but the major question relies if anonymous contractors of low professional status are able to win the trust among customers. If not, customers will organize the food delivery themselves. Moreover, both the taxi industry or food delivery services are fragile for any incident of being part of the chain of virus contagion. As delivery workers operate with low pay risking them to work when ill, they can also spread the infection to vulnerable people.

The COVID-19 epidemic is a test of trust between customers on one side and companies, employees and contractors on the other.

Couriers are at risk of losing their incomes partly or completely, when they fall ill. If couriers take deliveries to sick people, they also risk their own health. Uber and other platform taxi drivers face even greater risks staying with customers in vehicles. They have no option of contactless driving so the risk of getting the virus might be greater. Furthermore, Uber/platform drivers already lost most of their income generated by rides to airports or to work during rush hours with “high demand” increased prices, or to mass events and weekend night fun in most parts of the Northern hemisphere. Unlike the food carriers, many Uber drivers have invested in expensive means of production – their cars. They have loans or car rent to pay.

While many delivery workers combine their work with studies or other jobs, the situation with drivers is different. In Russia the majority of drivers work on a rented car with a daily rate that takes about 1/3 of their usual daily earnings. In Finland the majority of taxi drivers are entrepreneurs driving leased cars with obligatory monthly payments. Drivers for whom driving is the only source of income are at greater risk of losing both the work and their cars.

Opportunities and long-haul perspectives

The unexpected public health emergency is likely to lead to a severe economic recession, and therefore the decided state support for small business holders is an essential and viable short-term solution. In the emergency the government of Finland finally might recognize the unsecure position of the solo-entrepreneurs and the self-employed. On a longer haul, this crisis could even mean a push to develop security schemes for vulnerable workers, both the platform economy workers and the self-employed like freelancers.

Some of the platform taxis companies offer sick pay schemes that compensate income loss during the COVID-19 pandemic related to sick leave among already vulnerable platform economy drivers. Uber and Lyft have already demonstrated coordination in developing the counter crisis measures. Broader cooperation between the platform companies and the authorities may help to develop consistent policies and crisis management tools for future challenges in a way which also takes into account workers’ need for social protection and related security schemes.

This crisis could even mean a push to develop security schemes for vulnerable workers, both the platform economy workers and the self-employed like freelancers. Broader cooperation between the platform companies and the authorities may help to develop consistent policies and crisis management tools for future challenges in a way which also takes into account workers’ need for social protection and related security schemes.

Taxi sector, including the taxi platforms, have lost a lot of customers when mobility has decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is likely to take several months before the rhythm of the city life returns to normal. Before that, some taxi drivers who try to win trust among customers with extensive hygienic procedures. Furthermore, the media have reported increased pressures within the taxi-sector as some taxi companies give health professionals 50% off the normal price to ensure that key national workforce stays healthy during the severe epidemic. Another taxi-company has responded with an offer of 1000 free rides for the health workers dealing with Corona patients in Helsinki. Does Uber and Yango (under this brand the Russian Yandex.Taxi operates in Finland) respond to competition with special offers?

Some platform business suffers, but also some new opportunities open. Taxis – both traditional and the application based operators – seek new markets in food delivery as governments require quarantine like behavior from seniors and the vulnerable. The restricted mobility means that a safe grocery and food delivery should be organized a way or another, and now taxis have free capacity ready, both manpower and vehicles. Free taxi capacity due to the COVID-19 has led to Taxi Helsinki, the largest chain in Finland, to offer a grocery delivery from a customer’s local supermarket at a flat rate of 20 euros. The trust among the public is a decisive factor for the grocery and food delivery services. Winning societal trust in the fragile situation, these services could utilize health professionals in shaping the hygieny of their processes during the COVID-19 era.

Towards responsible platform economy

Rapidly expanding across the globe the ride-failing platforms demonstrated two common trends. Firstly, while Uber and other services adapt to local legal context they often exploit the gaps and grey areas in legislation. Secondly, transportation platforms are usually highly concerned about the public image of their service especially in the safety aspects. They usually quickly respond to raising challenges by introducing the various technological means of control and shifting much of responsibility on drivers. At the time of COVID-19 pandemic it is important that platforms also demonstrate their responsibility for those whose welfare and wellbeing depends on these platforms.

References

Isaac, E. (2014). Disruptive innovation: Risk-shifting and precarity in the age of Uber. UC, Davis. BRIE Working Paper. 2014-7.

Srnicek, N. (2016). Platform Capitalism. Polity.

World Economic Forum (2019) The Global Risks Report 2019. 14th edition.

Zwick, A. (2018). Welcome to the gig economy: neoliberal industrial relations and the case of Uber. GeoJournal. 83. 679-691.