The COVID-19 pandemic and the measures adopted by many governments and cities resulted in slowing down urban life, closing businesses, and locking people into their homes. Social distancing works for public good and it increases the need for efficient grocery and food delivery services. These services help solving public health problems though they include critical health and social protection aspects themselves.

Increased demand for grocery delivery

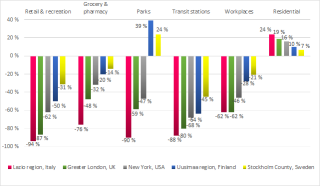

Most typically, the ‘flatten the curve’ policy included various limitations on mobility of people (without interrupting transportation of goods), closure of educational premises and other public venues. Private services such as restaurants and bars can either be ordered to complete closure or their kitchens are allowed to serve food to clients at home through various delivery platforms. Many countries, regions and cities have gone into a complete lockdown or even curfews. The reports published recently by Google or Apple demonstrate COVD-19 epidemic affected urban mobility in various parts of the world.

Picture 1. Changes in urban mobility on March 29th, 2020 when compared to a median value for the corresponding day of the week, in early February in Lazio region (Italy), Greater London (UK), New York (USA), Uusimaa region (Finland) Stockholm County (Sweden). Source: Google COVID-19 Community Mobility Report).

When people are advised to stay at their homes for longer period of time this eventually leads to an increase in demand for delivery services: someone has to bring groceries, ready food, medicine and other online purchases to people at their homes. In the US, Russia, and some other countries the governments have defined delivery work as part of essential critical infrastructure at the time of crisis and allowed delivery people (who can confirm that they carry on their assignments) freely move disregards the lockdowns (CISA, 2020)

Delivery workers are among the most exposed to contracting virus as they move around the cities carrying deliveries to dozens of customers in a day.

We assume that at the time of the epidemic the delivery workers are among the most exposed to contracting virus as they move around the cities carrying deliveries to dozens of customers in a day.

Picture 2. Leading participants in the online food delivery market in 2018. Frost & Sullivan

In different countries, the online grocery stores and product delivery services have developed at different pace. The demand for delivery services is growing along with the growth of online retail of food and grocery across the globe.

The US the leaders of the delivery market are Doordash, Delivery Heroes, Postmates, SkipTheDishes (Picture 2). In Europe among the leaders of the delivery market are Deliveroo, Delivery Hero, Foodpanda, Uber Eats and Just Eat. In Russia the food and grocery delivery market is dominated by two IT giants Yandex (Yandex.Eda) and Mail.Ru (Delivery Club). In China Meituan-Dianping and Alibaba Groups’s Elle.me control most of the Chinese food and grocery delivery sector.

Before the epidemic, the online market of food and groceries had only 3% share of all online retail in Finland. However, food and groceries was the fastest growing sector of online retail with 37.4% growth in 2018-2019. Two companies Kesko and S-Group control over 80% or all of the grocery market in Finland. They work predominantly with transportation companies and entrepreneurs as contractors for grocery delivery. Their most typical online grocery shopping attracted wealthier families with children, and elderly. Helsingin Sanomat reported March 30th that during just two-three weeks of epidemics the online grocery shopping and home deliveries have increased 2-2,5 fold for S-Group and even 4-times for Kesko. Customers have to wait several days up to a few weeks for their home deliveries.

In forerunner the US many retail chains and delivery companies have announced that they will be hiring more warehouse and delivery workers: Instacart – 300 000 workers, Domino’s Pizza – 10 000, Walmart – 150 000; Amazon – 100 000 (also announcing increase of the minimum wage from $15 to $17). Inkstone, the South China Morning Post’s digital news brand, reports that Chinese food delivery infrastructure was well developed before the coronavirus epidemic, but during the crisis the industry showed its capacity at the peak demand. Both increased manpower and high-tech solutions up to drones and self-driving cars were utilized in delivering food.

The largest food delivery platforms that work with restaurants in Finland are Foodora and Wolt. Following the global trends, it is difficult to expect that this sector will demonstrate growth during the epidemic in Finland. Wolt has reported a moderate increase in order volumes in March, 2020, however, it could not determine if this was Covid-19 related.

In contrast to the fairly positive situation within food delivery, the closure policies resulted in significant decline of taxi rides. Many drivers working in traditional taxis or with ride-hailing platforms were left without a job. Reacting to this rapid change in the taxi market, Taksi Helsinki opened grocery delivery services using the existing taxi infrastructure. A consumer can call the taxi operator or use a website to send a shopping, after which the driver does the shopping adding to the grocery bill the delivery fee of 20 euros.

The epidemic disrupted the food-delivery networks as many restaurants were closed and customers were concerned about the safety of food and delivery people. On the other hand, delivery of groceries have seen strong growth and delivery companies are hiring workers and taxi entrepreneurs to transport goods.

Also ride-hailing platforms switch to deliveries. Bolt has reportedly launched contactless grocery delivery in Czech Republic and Slovakia where ride-hailing was completely banned during the epidemic. In Russia the Yandex.Taxi offered drivers options of door-to-door and courier deliveries. In France, Australia, UK and Spain, UberEats partnered with various grocery stores to include grocery delivery services to their current food delivery. After the coronavirus epidemic shattered the demand for taxi rides in China, the ride-hailing company Didi Chuxing launched delivery service.

The impact of COVID-19 epidemic was a mixed bag for delivery services across the globe. The epidemic disrupted the food-delivery networks as many restaurants were closed and customers were concerned about the safety of food and delivery people. On the other hand, delivery of groceries have seen strong growth and delivery companies are hiring workers and taxi entrepreneurs to transport goods.

Vulnerability of delivery workers

The platform economy relies on the work of those whom they call contractors (Srnicek 2016; Zwick 2018). The food delivery companies that apply effective digital platform technologies use gig workers as their workforce. This means that food delivery workers / couriers are freelancers or entrepreneurs, who are not entitled to the regulation that is typical for salaried workers. They must work according to the terms and conditions of the platform, with no bargaining rights. As entrepreneurs, they lack or have limited social protection, meaning they are not entitled to paid sick leaves. Additionally, platform work does not provide occupational safety and health (OSH), meaning it is the responsibility of the entrepreneur to ensure that their working environments are safe for their health. In relation to the ongoing pandemic, these aspects are most likely to influence the way couriers respond to their work.

The food and grocery delivery workers move in the cities meeting dozens of clients, visiting many restaurants, grocery stores or warehouses. They are at higher risk of being infected. Due to varied symptoms among COVID-19 carriers, some of the workers may not be aware that they are carrying the virus. They may continue to work even with mild symptoms. When working with some platforms (for instance Foodora) getting new work shifts depends on worker’s performance and activity ratings. These ratings rapidly drop if a worker chooses to stay at home for several days in self-quarantine. Reporting to the platform company that gig-worker is on self-quarantine may lead to suspending of the worker’s account.

When working with some platforms (for instance Foodora) getting new work shifts depends on worker’s performance and activity ratings. These ratings rapidly drop if a worker chooses to stay at home for several days in self-quarantine. Reporting to the platform company that gig-worker is on self-quarantine may lead to suspending of the worker’s account.

There were several cases when Amazon and Instacart grocery delivery workers went on strike demanding better protection: paid sick time off (now applied only to gig-workers who have tested positive for the coronavirus or get placed on mandatory self-quarantine), better workplace safety (cleaning and sanitation), better pay to offset the risk they are taking, additional $5 per order and free hand sanitizers, disinfectant wipes and soap. Earlier Deliveroo announced that the platform provided free hand sanitizers and face masks to its employees.

Platform workers are constantly under surveillance, their movement is tracked, their work performance is constantly evaluated by platform algorithms and customers. Platform workers are part of the precariat, with great unpredictability and little autonomy and security. (EuroFound 2018; Lee et al 2015). A pandemic with novel risks and worries adds another negative layer on psychological welfare: the safety concerns about the interactions with clients and aggravated by increased work intensity and shorter breaks (Jantunen 2017; EuroFound 2018).

The Washington Post illustrated this situation in their interview with a delivery worker who experienced emotional stress after contacting a sick person. They quoted him as saying, “if I was in a position of authority, I would personally say that food delivery should be shut down nationwide, that’s just my opinion”.

Similarly, on the other end, customers are also afraid of contracting the virus from food delivery persons. Public Health England has recently published a guidance for food businesses affirming an impossibility that the virus can be transmitted by exposure to food or food packaging. In response to the concerns of delivery workers and customers, delivery companies have introduced contactless deliveries. When a sick delivery worker is under pressure of getting his or her only income, and is afraid of being suspended by the platform if he or she applies for sick leave, one can’t exclude a possibility that some of them will continue to work being ill. If a courier is sick, the contactless delivery won’t be an effective barrier for spreading the virus.

Falling into a difficult position is documented by a reported case of Instacart courier who was advised by her doctor to isolate at home for having showed mild symptoms of COVID-19. Even though she later got tested when her symptoms worsened, Instacart still insisted that she did not qualify for any sick leave pay until results were out to prove that she was indeed positive of the virus.

Protection of gig-workers

The platform economy (particularly in transportation and delivery sectors) is based on principles of low cost and high efficiency. Usually this is achieved through reduction on expenses, expansion of services (both by increasing the number of customers and gig-workers), large volumes and high intensity of work. Adding 5$ per order or any additional expenses on worker’s protection can undermine “low cost and high efficiency” principles of platform economy. To help these gig-workers and solo-entrepreneurs suffering substantial reduction of customers and work, some governments announced extensive support packages for the period of COVID-19 epidemic.

The Social Insurance Institution, KELA, has had a relevant social security scheme before the arrival of the epidemic. A particular sickness allowance on account of an infectious disease is paid if a person has been given an order of isolation, quarantine or enforced absence from work because of an infectious disease. After presenting the doctor’s statement as evidence, this scheme gives full compensation of a salary. But in case of the couriers working with the platforms as freelancers or entrepreneurs their benefits are calculated based on their individual social insurance payments. As a result, their benefits are often small compared to ones of the full time salary workers. This is why the sick pay schemes of the enterprises have an important role in securing workers’ incomes.

As a new compensation media reported on 31 March that the government of Finland had introduced a flat sum of 2000 euros benefit scheme for those solo-entrepreneurs and freelancers, whose business is substantially weakened by the Corona crisis. Furthermore, the government of Finland extended the basic level unemployment benefits temporarily available for the entrepreneurs. The scale of problems within food delivery during the epidemic determines if or not some couriers can rely on these new schemes.

During these extraordinary times the US federal government adopted a historical CARES Act. It provided a social safety net for the self-employed gig workers. Freelancers can get an “additional $600 a week in unemployment insurance, bringing weekly payouts to the $800- to $900-a-week range when state benefits are added, to workers including the self-employed, for up to four months”.

In the UK, the government offered 330b£ to businesses hit by COVID-19, and self employed people like platform workers were first proposed a very low compensation of 94.25£/week. A few days later also the self-employed were treated equally to salaried employees who were entitled to compensation of 80% of the salaries up to 2500£/month. Millions of people across the UK could benefit from the new Self-Employed Income Support Scheme, with those eligible receiving a cash grant worth 80% of their average monthly trading profit over the last three years. It is a unique achievement from a social protection scheme (to be in force at least three months) that it generously covers 95% of the self-employed workers.

Greater attention to working conditions

There is high demand for home deliveries including food and grocery deliveries due to the global pandemic that has confined people in their homes. This has in turn resulted in increased workload among couriers and other delivery workers. While various platforms have announced employing more workers, some companies have taken the advantage of the situation and added deliveries to their services. This high demand for deliveries has resulted in workload stress among couriers, affecting not only their physical wellbeing but also their mental wellbeing.

Social distancing, temporary closures of restaurants, schools, shopping malls offices help to save lives during COVID-19 pandemic. In a rapidly changing situation innovations and new practises have a potential to flourish. Intense service culture has been common in the world’s metropoles. In future even Finland, known for its self-service orientation, may take steps towards an indemnification of service society. The delivery platforms that have been applying digital technologies in their business are a few steps ahead. Also well established service companies are entering the field. Taxi companies that suffer a lack of customers are finding new markets from grocery delivery. Overall, the COVID-19 crisis with massive increase in demand enhances development of food delivery.

Although concerns have risen whether the food left at a doorstep / entrance is safe from COVID-19, it is meritorious that delivery organizations / platforms have taken precautions towards minimizing the spread of the virus. It is therefore upon the consumer to think of better ways to receive their food, for example they can offer a storage box by their doorstep or entrance in which the courier can place the food. Prevention of spread COVID-19 is the duty of everyone. The fight against the spread of COVID-19 in the food delivery sector should not be left only for platform workers but restaurants and consumers must be equally responsible in enhancing and ensuring healthier practices.

In the long run COVID-19 epidemic has facilitated growth of otherwise underdeveloped grocery delivery services.

In the long run COVID-19 epidemic has facilitated growth of otherwise underdeveloped grocery delivery services. Accordingly, some platform companies presented flexibility of switching between types of business (from transportation of people or food to transportation of groceries). This shows that the sector has the potential of creating new workplaces in a longer run. It is also important that the digital platforms and also governments learn from this crisis and pay greater attention to work conditions and rights of gig-workers. An important lesson is that several platform companies demonstrated a common approach in offering workers sick leave pay guarantees. The temporary crisis time social security schemes in Finland, and particularly the substantial compensations in the UK, show that also self-employed can be protected against social risks.

References:

CISA (2020) Memorandum on Identification of Essential Critical Infrastructure Workers During Covid-19 Response. The Department of Homeland Security. Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency. March 19, 2020.

Eurofound (2018). Employment and Working Conditions of Selected Types of Platform Work. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. ISBN: 978-92-897-1749-6. Last updated on 23 September 2019.

Jantunen, R. (2017). Does the Worker Have a Say in the Platform Economy? Time of Opportunities Project. SAK, The Central Organisation of Finnish Trade Unions. Retrieved on 19th April 2020 from:

Lee, M.K., Dabbish, L.A. & Kusbit, D. (2015). Working with Machines: The Impact of Algorithmic and Data-Driven Management on Human Workers. Conference Paper: CHI ’15 Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Research Gate, DOI: 10.1145/2702123.2702548.

Srnicek, N. (2016). Platform Capitalism. Polity.

Zwick, A. (2018). Welcome to the gig economy: neoliberal industrial relations and the case of Uber. GeoJournal. 83. 679-691.