Segregation within cities leads to social inequality, blocked educational and employment opportunities, poor infrastructure and lower quality of housing conditions. These factors alienate people from achieving the 11th Sustainable Development Goal, titled “sustainable cities and communities”, and are created by the United Nations along with 16 other goals to provide guidance for governments to build safe, inclusive, and resilient cities. But how do we define a sustainable city?

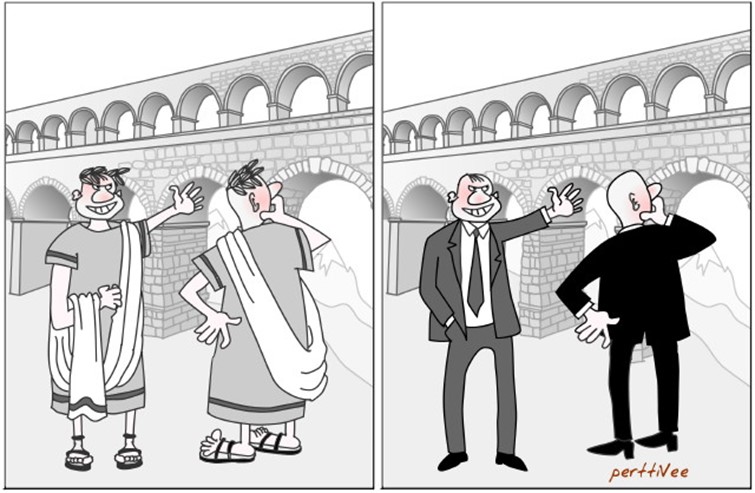

It is a common mistake to use “sustainable” and “eco-friendly” or “smart” as interchangeable concepts. Even though sustainability covers both innovations and striving for green alternatives, it does not end on those aspects. At Urban Studies Conference at Tampere University Professor Vishanthie Sewpaul, defined sustainable cities as ones where people live a happy and healthy life in peaceful co-existence between themselves and the surrounding environment. Citizens should have access to basic resources, build social trust, have distributive justice and non-discrimination in all forms. Building sustainable cities also requires transparent government and civic participation. It should be a city where people feel freedom from the constraints of one’s own thinking, freedom from prejudices, and freedom from the past.

Durban is a post-apartheid city located in South Africa. Apartheid in South Africa is a systemic racial segregation, while post-apartheid is the period after the discrimination ended in 1994. Its population is 3.7 million with 51% being black African, around 25% are Indian or Asian, 15.3% are white, and 8.3% are designated as colored. Transforming Durban, South Africa’s third largest city, to be sustainable is quite tough. During apartheid period colored people were forcibly relocated to create homogenous distribution of neighborhoods. Residential areas were isolated from each other with natural and constructed boundaries like railways, highways, and rivers.

Main issues that the population of Durban faces include unsafe environment, especially for women, even from the side of police workers, who should protect people from danger but instead are the danger themselves.

Main issues that the population of Durban faces include unsafe environment, especially for women, even from the side of police workers, who should protect people from danger but instead are the danger themselves. Beaches and entertainment centers were constructed to serve rich white people with privilege in power, creating a gap between them and other socioeconomic groups. Governmental corruption and money leaks slow down the city from developing further. Young people willing to work fail to find a proper job and work as car guards or try to sell something to tourists, which unfortunately became rare due to the pandemic’s travelling restrictions.

On the other hand, Durban is also a city that has improved and grown over the years.

On the other hand, Durban is also a city that has improved and grown over the years. It is the leader among African cities for tracking greenhouse gas emissions, has very good infrastructural development, and its internet access has grown steadily over the years, although it still is too low, with only 3.4% of population having fixed Internet at home, while rural home access is equal to 0.4%. The cost of having fixed internet in South Africa is 899 rand (53.9 euros) so the distribution gap comes as no surprise. Nevertheless, South Africa is the 3rd most biodiverse country in the world, while Durban was described as one of the 35 “biodiversity hotspots” globally and work has been put in to preserve it.

Because of South Africa’s history with apartheid and segregation, racial segregation is still easily observed, as white population owns 87% of the land; however, now the segregation levels are also high between low-income and high-income classes. It affects different fields of life, like access to education, job opportunities, health and wellbeing of people and even how harsh climate change consequences they would experience. The inequality results in reduced life expectancy and higher infant mortality to poor educational attainment, and increased levels of violence within the city.

The first people to feel the effects of climate change are the ones that contribute to it the least. The rich contribute to climate change every day by driving cars, flying around the world and increasing their carbon footprint.

Durban city is planned as a dream for the rich white man, having modern hotel buildings, coastline and white beaches. By the 20th century, the city was a major port and after the end of the First World War it was transformed into a metropolis to accommodate rich white business owners.

We were astonished by realizing that the Durban city is planned as a dream for the rich white man, having modern hotel buildings, coastline and white beaches. By the 20th century, the city was a major port and after the end of the First World War it was transformed into a metropolis to accommodate rich white business owners. In order to make that dream come true, greenhouse gases are pumped into the atmosphere and lungs of people with lower income, residing on the other side of the same street. Because low-income people can’t afford to live in areas with clean streets and fresh air, they have no choice but to live in poorly structured neighborhoods without proper resources and inadequate public spaces. Low-income neighborhoods are not built to withstand natural disasters like wildfires, rising sea levels or oil spills. This is just another example of the stark differences between people in one city, even in one street, but on different sides of the road, like Cato Crest and Glenwood.

Each of us is responsible as an individual and as a society. The power of one is the power of many. People should strive to lead the building of their city and their future, not to follow someone – governance instead of government. A tree leaf, presented by Professor Vishanthie Sewpaul, demonstrates the interconnectedness of factors needed to make something small happen. The leaf became what it is because of sun, water, wind, people planting the tree, people watering the tree, and the tree itself, meaning that a lot of factors contribute to making something small exist. This metaphor was a descriptive example of how every person can contribute to making a change, while slight changes lead to greater changes. Anything is possible if at least one person holds the hope for the best and shares it with others. We believe all the readers will believe that opportunities of making cities a better place to be, are in their hands.

Inclusivity of public spaces would build a safe environment inside the city and increase interaction of people from different backgrounds with each other.

Our blog post was inspired by the keynote session of Vishanthie Sewpaul in the Urban Studies Conference at Tampere University, where we understood that there is enormous room for improvement in the field of Sustainable Urban Development and City Planning. A lot of environmental, economic, social, cultural, and historical aspects should be considered for urban development. The historical background of the city would help to find optimal ways of replanning the urban area to cover the needs of different social classes and eliminate past segregation footprints. Inclusivity of public spaces would build a safe environment inside the city and increase interaction of people from different backgrounds with each other. Economic aspects include the potential of the city to create revenue, while providing affordable prices for living.

All these factors considered in a holistic approach would build a sustainable city of the future because city planning in the 21st century is not about buildings and streets; it is about people and their wellbeing.