This text contains spoilers for the game Firewatch.

Melissa Kagen argues that Firewatch shines a light on the issues of toxic masculinity in gaming and lets the player perform a more nuanced form of masculinity.

In her article “Walking, Talking and Playing with Masculinities in Firewatch”, Melissa Kagen examines the game Firewatch and how it problematizes toxic masculinity. Kagen details how Firewatch, through its gameplay and narrative, subverts and problematizes the performance of toxic and narrow hypermasculine tropes common in videogames.

Kagen starts by discussing certain forms of masculinity in gaming and their prevalence in general. She writes about the performative nature of masculinity – the notion that “’acting like a man’ defines what men act like”. She further expands this to view masculinity in a constant state of change, shaped by both social and technological factors. Kagen uses three key terms: hegemonic masculinity, hypermasculinity, and toxic masculinity. The first refers to masculinity being “defined by a set of normative traits and behaviors” and being used to guarantee the dominant status of men over women. Hypermasculinity, in turn, refers to masculinity being reduced to a small set of extreme traits derived and intensified from hegemonic masculinity. Finally, toxic masculinity covers the ways in which hypermasculinity is harmful to society at large.

Hypermasculinity in gaming is often connected to capitalist values, such as measuring one’s worth by their productivity. This could be contrasted with geek masculinity, which values technology and gaming itself, presenting itself as an outcast that rejects both the feminine and the traditionally male. Kagen, however, explains that geek masculinity is rather just the evolution and continuation of hegemonic masculinity – mirroring our culture’s emphasis on technical mastery and dominance. She also notes that videogame design often promotes hypermasculinity via aggressive and stoic traits, leaving out other types of masculinities. As a result, a significant part of male-identifying gamers feel that they are not in the target audience for games and don’t feel represented in them.

Firewatch is a game about Henry, a man escaping his troubles to work as a fire lookout in Wyoming. Throughout the game Henry – communicating via radio with his boss, Delilah, in a nearby lookout tower – runs into mysterious events that end up not being what they seem at first. The genre of the game being a walking simulator, Firewatch strays from hypermasculine gaming tropes already in its exploration-focused design. It is not focused on action and goals, but instead relative passivity and calm exploration. This is opposite to two central hypermasculine traits: domination and self-reliance.

Henry exhibits many traditional, hypermasculine traits but the player is not allowed to act on them. They are instead directed toward playing a less one-dimensional, more developed male protagonist. Kagen explains that Firewatch “plays with the tension it creates between the player’s desire to control the world (a common videogame expectation and a central tenet of hypermasculinity) and Henry’s lack of control”.

Situations tend to develop into a different direction than the player intended, forcing them to contemplate and talk out the resulting feelings meaningfully, instead of simply reacting by action. These aspects are shown first in the prologue of the game, where most agency is taken away from the player – reflecting the narrow limits of 80’s’ straight masculinity. Another aspect of this is the conversation mechanic, where the player doesn’t have full control of when the conversations end and begin, and where the conversational choices may differ somewhat from the end result. Delilah reacts to Henry trying to avoid a conversation and Henry periodically fails to control his emotions, reacting more drastically than the player intended. Henry’s – and the player’s – sense of paranoia and tendency to find mystery, achievement, and adventure where there is none also reinforces the game’s focus away from action. This is because the game eventually reveals that the mysterious dangers were rooted in real-world challenges that require care-oriented skills like conversation and patience, rather than action and violence.

Instead of hard work through skill-based prowess and achievement, Firewatch highlights the importance of emotional labor and facing real-world problems instead of running from them. Kagen also uses the controversial YouTuber PewDiePie as an example of the community reaction to Firewatch and especially its ending – disappointment at it lacking the achievement of productivity and other traditionally masculine values (like the “getting the girl” trope). In conclusion, Kagen argues that Firewatch uses the language of toxic geek masculinity to subvert traditional videogame expectations and to deliver an experience that reflects masculinity in a more complex and nuanced way.

Original article: Walking, Talking and Playing with Masculinities in Firewatch

Author and institution: Melissa Kagen, Bangor University

Publication: Game Studies, Volume 18, Issue 2

Published: September 2018

Online: http://gamestudies.org/1802/articles/kagen

You might also like

More from Game Research Highlights

How do you want to do this? – A look into the therapeutic uses of role-playing games

Can playing RPGs contribute positively to your wellbeing? A recent study aims to find out how RPGs are being used …

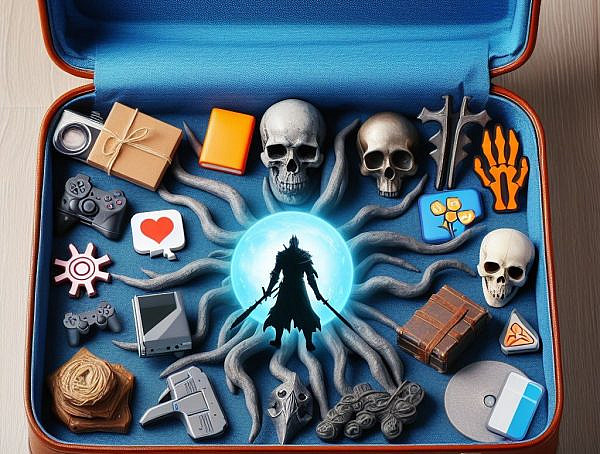

Eldritch horrors and tentacles – Defining what “Lovecraftian” is in games

H.P. Lovecrafts legacy lives today in the shared world of Cthulhu Mythos and its iconic monsters. Prema Arasu defines the …

Are Souls Games the Contemporary Myths?

Dom Ford’s Approaching FromSoftware’s Souls Games as Myth reveals the Souls series as a modern mythology where gods fall, desires …