Women are represented through various misogynistic tropes of monstrosity and consequently dehumanized in the bestiary of Dungeons & Dragons, the Monster Manual, that has subsequently influenced the mechanics of digital role-playing games, demonstrate Sarah Stang and Aaron Trammell in their article The Ludic Bestiary: Misogynistic Tropes of Female Monstrosity in Dungeons & Dragons.

Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) was designed and created for a niche group of “gamers” by what the researchers call a boys’ club. According to them, this is reflected in the game’s rules and mechanics. The Monster Manual (MM), first published in 1977 and originally written by Gary Gygax, is a core guide to monsters that can be used in D&D games. It presents a collection of illustrated monsters, similar to medieval bestiaries that recount descriptions of real and imaginary creatures.

Stang and Trammell found that the MM creates a game mechanic they call the ludic bestiary. The format of the ludic bestiary combines images, descriptions of culture and behavior, and statistics to create monsters for a game world. Ludic bestiaries have since been used in digital role-playing games, for example, the God of War and The Witcher series.

By analyzing the hag that appears in all editions of the MM, the researchers found that the moral order of the MM is misogynistic due to the representation of women through tropes such as deception, monstrous motherhood, and insidious sexuality. These echo the historical traditions of medieval bestiaries and European witch hunts. The researchers contend that by describing female monsters as though ‘scientifically’, the MM normalizes the idea of female bodies as abject.

According to the research, medieval bestiaries were policed by Christian morality and used as tools to create moral allegories by reducing non-normative subjects to animals and classifying their bodies as evil. Previous research on monstrosity has found that monsters like those in mythology, fairytales, and popular culture have many functions, including othering groups of people and embodying cultural anxieties.

Stang and Trammell present that maternal and menstruating female bodies have culturally been seen as abject and that the idea of abject female bodies is reinforced through deceptive and vulgar female monsters. In the article, the abject is understood as all that is disturbing to the normative patriarchal order and thus feared and rejected, although also seen as intriguing. The abject is, for example, death, wounds, bodily fluids, disease, cannibalism, and sexual perversion.

Of the female monsters in the MM, the researchers have chosen the hag as a case study. The fifth MM (2014) describes hags as withered crones, despite their immortality, whose evilness is reflected in their appearance as warts, moles, and frayed hair. Stang and Trammell found that the description closely resembles the centuries-old ageist and sexist image of the witch in Western society. Witches were believed to steal children because they couldn’t have any; a belief that is renewed in the MM that states that hags steal and eat babies to give birth to daughters that will one day transform into hags as well. Hags are also described as deceptive and manipulative since they can alter their appearance, and it is said that they form covens with other hags.

The researchers demonstrate that the hag is an example of gendered monstrosity that reveals hostility and fear towards societies of women and female aging and reproduction. They argue that, in the bestiary, the evilness and danger of hags stem from their power and uncontrolled form of motherhood, and that the MM thus stigmatizes female independence, intelligence, and strength.

Beyond the descriptions and images resembling medieval bestiaries, the MM gives monstrous bodies non-normative statistics, thus quantifying moral connotations. The various hag types in the fifth MM have higher than average strength, constitution, and charisma statistics, in addition to illusory abilities, high intelligence, and bonuses to deception checks. The researchers argue that the statistical values suggest the hag is monstrous because of her non-normative bodily capabilities that are in contrast with her ugly and withered appearance.

Stang and Trammell contend that the ludic bestiary produces abject bodies by telling players, via statistics, that it is the difference from the bodies of the players that makes the hag and other monstrous bodies horrifying. The ludic bestiary thus gives form to a new quantitative morality and becomes an instrument of subjugation through dehumanization.

Article:

Stang, S., & Trammell, A. (2020). The Ludic Bestiary: Misogynistic Tropes of Female Monstrosity in Dungeons & Dragons. Games and Culture, 15(6), 730–747. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412019850059

Photo:

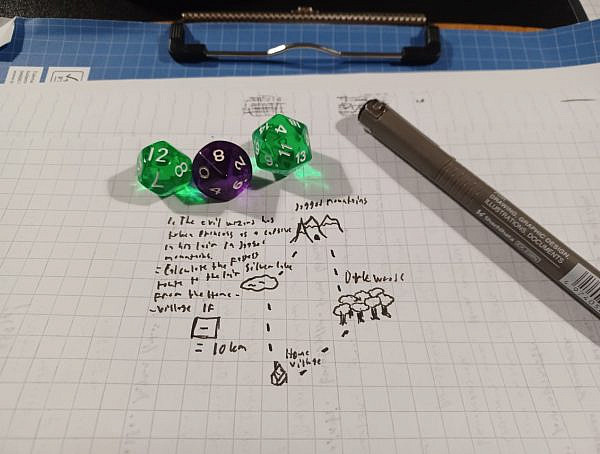

“Where are the Cheetos?” by Sharon Drummond is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

You might also like

More from Game Research Highlights

How do you want to do this? – A look into the therapeutic uses of role-playing games

Can playing RPGs contribute positively to your wellbeing? A recent study aims to find out how RPGs are being used …

Eldritch horrors and tentacles – Defining what “Lovecraftian” is in games

H.P. Lovecrafts legacy lives today in the shared world of Cthulhu Mythos and its iconic monsters. Prema Arasu defines the …

Are Souls Games the Contemporary Myths?

Dom Ford’s Approaching FromSoftware’s Souls Games as Myth reveals the Souls series as a modern mythology where gods fall, desires …