I first heard of Elite Dangerous when a friend told me about their experiences with the game. They described damaging their ship and being left adrift in the vastness of outer space. Core systems destroyed and oxygen levels falling, all they could do was wait for an inevitable death by asphyxiation. I was captivated by this scenario. It suggested a videogame that could offer experiences of scale and existential helplessness not usually available in a medium that tends to prioritise player agency. I bought it the next day with the idea that my friend and I could play together, only to discover that it doesn’t support cross-platform play. I tried it once by myself, struggled through a tutorial, and gave up in frustration when the sim-like controls didn’t immediately allow me to pilot my ship like a veteran dogfighter. I deleted it, promising myself that I’d return, but knowing the game was now likely to languish forever in my library.

In the time since, I’ve played several other games based around exploring outer space, however, those I spent most time with were Endless Space 2 and Stellaris. These offer a very different experience to Elite Dangerous. Theirs is the perspective of empire and its map – space as something to expand into, an empty territory to conquer and demarcate. I grew tired of both pretty fast. Although I’m usually a fan of the grand strategy and 4X genres, outer space doesn’t lend itself to what makes these interesting. Historical narrative, at the scale of a galaxy, is painted in too broad strokes. After initial excitement, the galaxies of Endless Space 2 and Stellaris felt flat and strangely domesticated, their forms reduced to abstract statistics that revealed the games’ mechanics beneath clichéd fictions. I missed the shifting landscapes of Civilisation and the counterfactual imaginaries of Paradox games.

I thought perhaps interesting experiences of outer space weren’t something that videogames are well-suited to produce. Space seemed too vast to allow for either satisfyingly detailed designed environments or narratives that unfold on a human scale – just look at the lifeless infinity of No Man’s Sky. There were games set in space that I loved, but these – such as Tacoma – tended to use space as a setting for what still felt like terrestrial narratives. They were not about the experience of space itself.

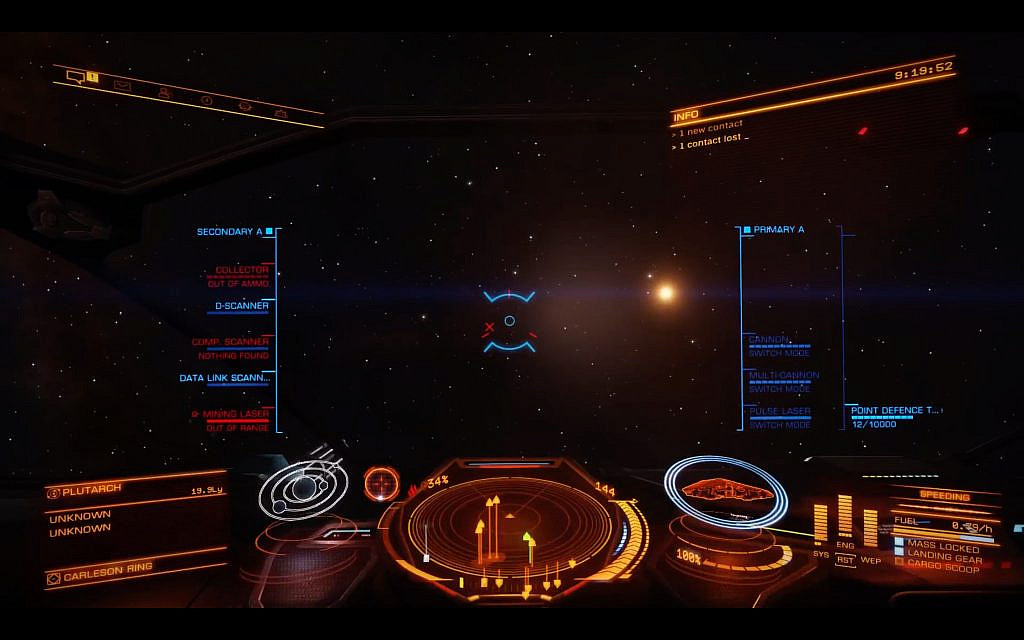

My ship, the Sviatagor, docked in the Carleson Ring Station. Not only space is navigated from the cockpit, but also the game’s various market places and menus.

This summer, however, two books opened my eyes to new experiences of both outer space and videogames, and also led me return to Elite Dangerous. The first was Brendan Keogh’s A Play of Bodies: How We Perceive Videogames (2018), which is interested in the role of players’ bodies during play, as well as the ways in which technology mediates and structures our experiences both in videogames and real life. For Keogh, humans are always already enmeshed within technologies that help to construct our understanding of our bodies and our worlds. Think, for example, of the way that a blind person uses a cane to perceive what lies in front of them. Technologies, he argues, form our subjectivities. We are all already cyborgs.

The other book was a Cuban sci-fi novel by Agustín de Rojas called A Legend of the Future. It takes place on an experimental spaceship making a test voyage to Titan. The ship is trialling a new propulsion system that allows for hitherto unimaginable speeds and thus relies upon sensors and an AI pilot to avoid collisions with meteors and other objects. On its return journey the ship is involved in an accident that kills three of its six crew, mortally wounds the survivors, and destroys the ‘brain’ of the ship’s AI. In an attempt to return the ship to Earth and save the data that the trip has produced, the brain of one of the surviving crew members is transplanted into the ship to replace that of the AI. This crew member becomes a human-spaceship cyborg. His senses and capabilities literally now those of the ship which has become his body. The book is wonderfully evocative in its presentation of the hostility of space and the psychological and physical difficulties involved in traversing it. It reminded me of my friend’s experience with Elite Dangerous and made me want to feel something of that myself.

When I began to play again a second time, what struck me was a new appreciation of the experience of traversing space itself. The void became more present, an existential frame by which to feel my own smallness. Moving from station to station, space becomes enveloping. Likewise, the means of my perception became a more prominent part of the experience. Although my first action in the game was to create a pilot avatar, this sat static in my ‘real’ body, the ship itself. Like, Isanusi, the crewmember turned spaceship in de Rojas’ novel, I initially struggled to orient myself within a new perceptual apparatus. Doing so within an environment that is largely devoid of visible objects or the fixed axes of terrestrial navigation can be pretty tricky! It was clear that human senses alone were not up to the challenge of outer space. I quickly had to adjust, therefore, to navigation mediated by the array of sensors, radars and other systems provided by the ship. Before I did so, I almost killed myself a number of times. On one occasion I flew to close to star, overheating and damaging my systems. Each time I would power up the hyperdrive to quickly put distance between myself and the star, it would begin to meltdown. I had to crawl away using slower propulsion systems until I was distant enough to engage the drive and escape. This was the experience of space I was seeking.

The void of outer space from the cockpit. Visible are radar arrays, speedometers, scanners, and system status readouts.

I spent the majority of my time with Elite Dangerous transporting packages from one station to another. Depending on how you chose to play, the game can be little more than an intergalactic Euro Truck Simulator. However, transposed from the banal realism of contemporary labour to that of science fiction, Elite Dangerous offers a form of speculative fiction that is arguably unique to the medium of videogames. It gives you both the chance of experiencing first-hand the both novel and quotidian cyborg consciousness of the human-spacecraft, as well as its perception of the void.

Developer: Frontier Developments plc

Publisher: Frontier Developments plc

Platforms: Xbox One, Playstation 4, Windows, Mac

Genre: Simulation

Rating: PEGI 7

All pictures used are screenshots taken by the author.

You might also like

More from Features

Game Awards – Celebration of talent or a Marketing Extravaganza?

The Game Awards 2024 is over and the winners are announced. However, are they still following the same pattern that …

Worlds in a Finnish Theater: League Finals, Community, and Döner Kebab

I travelled to Helsinki to watch League finals in a cinema, and it was worth it. #leagueoflegends #esports #community #worldfinals