If an eight-year-old student approached me asking how to calculate x on a triangle so that they can go save a fictional hamlet from evildoers, I’d think that something is terribly wrong in the classroom. On the contrary, a middle school teacher and PhD student Maryanne Cullinan has concluded that the use of tabletop roleplaying games (TTRPG) or roleplaying games (RPG), has untapped potential as a tool for education. According to their paper “Surveying the Perspectives of Middle and High School Educators Who Use Role-playing Games as Pedagogy” (2024), more research should be focused on this phenomenon. Furthermore, as Cullinan noted, there is a break in connection between the academia and educators which leaves those who use RPGs for educational purposes to fend for themselves.

To establish foundation for research, eleven teachers from three countries, USA, Canada and Cambodia were selected and interviewed by Cullinan. All of them used RPGs as part of their program and claimed success in using this method compared to the standardized forms of education. All of the interviewees worked in a professional setting, teaching children and young adults between the ages of ten to eighteen, some of which, according to the teachers, had rough lives or were exceptional learners. Another interesting finding about the teachers themselves was that they shared interest in RPGs and other gaming-related hobbies but had little to no academic guidance on how to implement these into their teaching. Rather, they had brought their beloved hobby into the classroom and wrangled it as part of the curriculum completely by their own choice.

Findings of the study were also reflected via Gary Alan Fine’s “Three Frames Theory” (2017), which divides the mental space of people who play roleplaying games into three separate layers, something that could be observed and analyzed by the teachers and the researcher.

The first social layer showed how playing the game as a group proved to be beneficial for the communal growth and togetherness of the students. The fictional world became an affinity place, term originally named by James Paul Geen (2017) where the students could safely engage in learning task via investigation, research and a little trial and error. This social structure of games created a need to work and learn new skills as a group, which in turn formed comradery among the students. The shared burden of tasks set before them and their fantasy characters caused children to learn how to better work with others and how to give room to others in tasks where their knowledge or skills benefited the group the most. According to the teachers this social structure in the fictional gaming-space made it so that everyone had their moments, and, in some cases, this reflected even as changes in the hallway behavior.

This social growth is also reflected in the second layer, which is the more tactile, mechanical layer. While the students left and returned to their fictional world, they became more and more task and duty oriented, eager to learn new skills and acquire knowledge to succeed in tasks that waited for their characters inside the game world. Because these tasks and more importantly, their progress was shared, there was a shift from individual students and their achievements to the achievements of the group. To win the game the students began to look after those who they shared the world with, something that reflected both their social growth and learning.

According to the research, these previously mentioned layers folded into the third, fictional layer. The shared world and the lenses of fictional characters impacted how students view their process of learning. The world and story within turned into a safe sandbox, in which students sought to progress as a group. This meant that they began learning new skills on multiple levels but driven by their own motivation, rather than need to gain better grades in school.

Maryanne Cullinan’ findings show that there is potential in letting the children play in the classroom, at least as long as the fiction is made in manner that it supports the official curriculum and offers a safe space to both learn and play. Their findings also add to the notion that more research and connection between the teachers and academic study related to the subject is required.

Cullinan, M. (2024). Surveying the Perspectives of Middle and High School Educators Who Use Role-playing Games as Pedagogy. International Journal of Role-Playing, (15), 127–141. https://doi.org/10.33063/ijrp.vi15.335

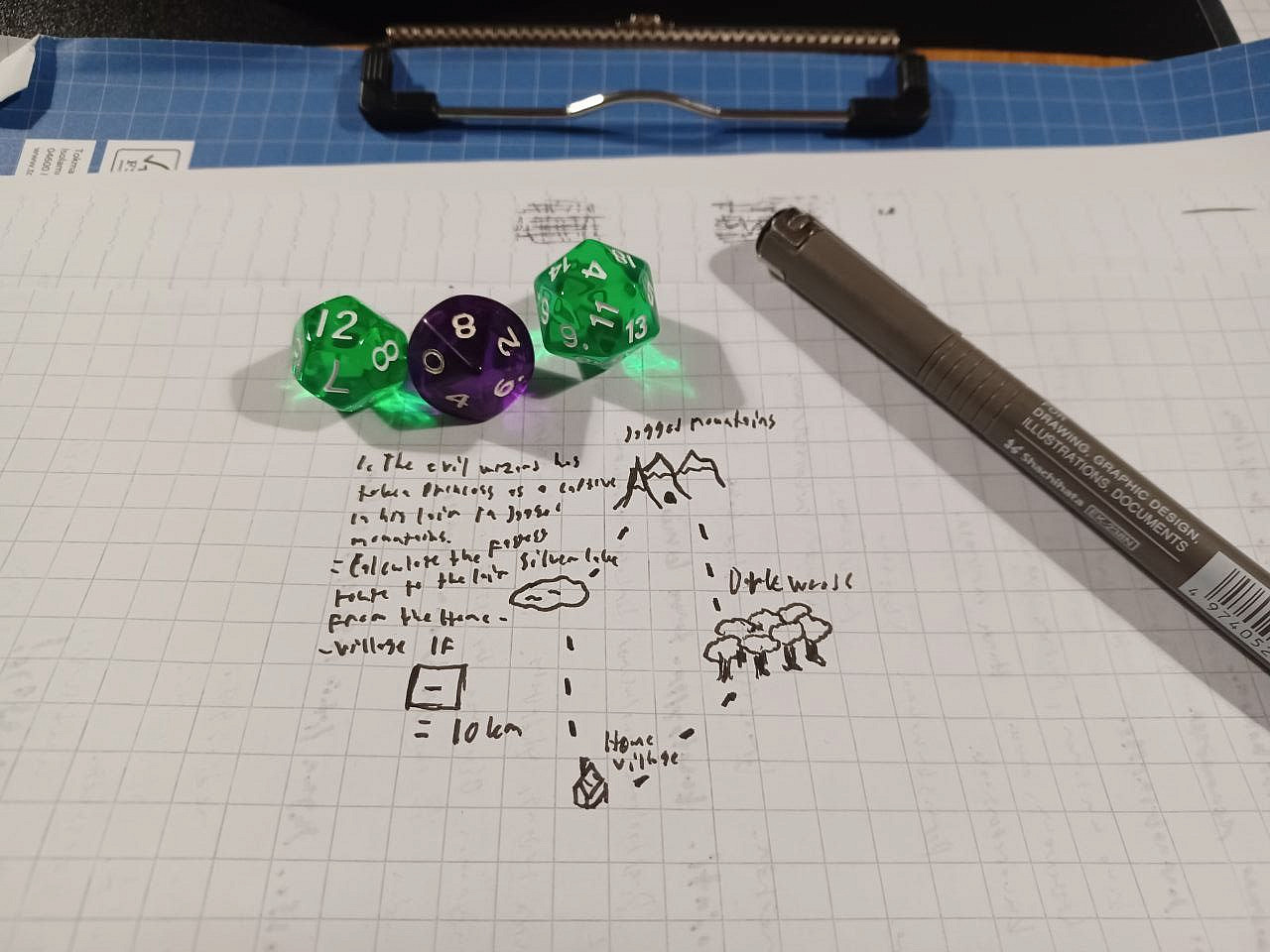

Pictures: Taken by the author (Samuli Siira).