Nicolas Poussin’s 1638 painting Et in Arcadia ego constructs a bucolic setting in which group of shepherds inspect a tomb inscribed with the words of the work’s title. The painting suggests that earthly paradise is inevitably still touched by death, that the latter’s fact is immutable and inescapable within our earthly lives, its possibility haunting even our most blissful moments and scenes.

In the future constructed by Phoebe Shalloway’s Even in Arcadia, Earth is no more than a legend. It is a fallen paradise, devastated and long ago abandoned by those rich enough to be able to leave for one of the new designer planets that are continually being constructed by those corporations that rule over an intergalactic humankind. Yet, even within these Edens beyond Eden, death’s spectre looms. The iron logic of capitalism demands constant growth and the creation of new markets. In a context of absolute material abundance, this means planned obsolesce on the scale of entire planets and the abandonment of those who cannot afford to move on to the next big thing.

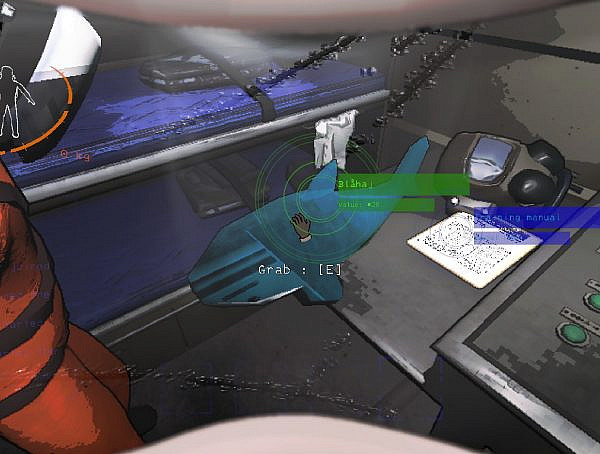

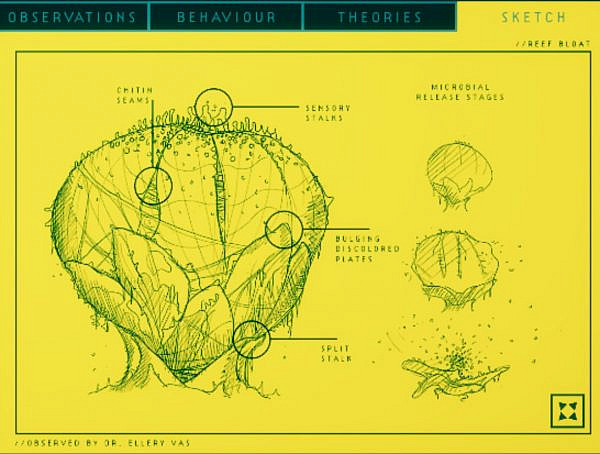

Despite its technical limitations – it was initially created as a Masters’ thesis project and is thus relatively janky – Shalloway’s game is aesthetically sumptuous. Set during the launch party for a new and improved Earth, the player moves through different prototype environments eavesdropping on the conversations of its many guests. Each environment is filled with gorgeous and often outlandish plants that are apparently the result of imaginative genetic engineering. Piped-in music adds depth to their atmosphere, and I particularly loved the use of choral song in the orchard.

The conversations of the launch’s various attendees mix personal and societal issues. They allow the player to get a sense of the wider world that the character’s inhabit, while also revealing much about the kinds of people that this world creates. Many of their problems, hopes, and fears are striking similar to our own, even if their outfits are far better. I enjoyed the degree of nuance within Even in Arcadia’s representation of what is nevertheless resolutely a dystopia. The worlds that the corporations are creating are undeniably beautiful. They are paradises of human design. Yet, these planets, filled with engineered organic life, are also designed to die. Likewise, humanity has become so alienated from the natural world that attendees must wear helmets while in the game’s environments. These maintain the sterile atmosphere in which people live aboard their ships.

It is clear that even some of those from Even in Arcadia’s ruling class feel trapped within a system that turns their best intentions and attempts to mitigate the harms inherent to their mode of life into a justification for and furtherance of that very system. It is tempting to see this as akin to the snare trap of late capitalism, whereby opposition is recuperated into the totality that it seeks to overturn. However, in the case of Even in Arcadia and its party of elite socialites and entrepreneurs, it appears more like a comment on the historical function of philanthropy. Members of the ruling class are unwilling to recognise that their economic and social power exists because of and can only perpetuate inequality. By providing a little aid to those that they exploit and harm in their quest for profit, they provide a moral salve that justifies the existence of the ruling class and the social order that allows it to rule – in the end, they know better than us how to spend the wealth we create. As some of the characters begin to realise toward the end of the game’s story, the only real hope lies in the (within the game very literal) worlds of the excluded and oppressed.

The kind of agency made available to those living within the society of Even in Arcadia is made amusingly apparent by the two modes of interaction that the game allows its players. These are ‘throw away’ and ‘consume’ – the two dominant modes by which the game’s society functions. For some players this will make the game something of an anathema. Commercial videogames have trained their players to expect to play the role of heroic agents. The player of Even in Arcadia isn’t even an important observer. They can listen and watch conversations, but they are not part of them, and the conversations happen regardless of the player’s presence. It is a piece of digital theatre, and, in that sense, is also perhaps a realistic portrayal of much of political life after the anti-democratic counter-revolution of neoliberalism. You are welcome to watch, consume, and discard. You can even choose who to follow, but the story will play out regardless and don’t expect to see those who pay the price.

Publisher: Pheobe Shalloway

Developer Pheobe Shalloway

Platforms: Mac OS and Windows

Release Date: 2019

Genre: Experimental, Indie

PEGI: N/A

All images are screenshots taken by the author.

You might also like

More from Game Reviews

Kingdom Come: Deliverance II – A Sequel Worthy of a Knight

KCD II delivers a living, breathing medieval roleplaying game to its players. #RPG, #kingdomcome, #openworld

Moncage Review: A Puzzle Game with Mind-Boggling Optical Illusions

Solving a huge #optical_illusion #puzzle in a tiny cube to discover a dark, #emotional story of trauma

Mining, Mayhem, and Bugs: A Deep Rock Galactic Review

Fight monsters, mine riches, and cause chaos with your dwarf crew — welcome to Deep Rock Galactic!