In his article Paradox and Pedagogy in The Stanley Parable author Antranig Arek Sarian examines the inherent, but often hidden, restrictiveness of pre-built storylines in games and other media that utilize interactive narratives. Sarian describes that The Stanley Parable “reveals the implicitly didactic voice that lies behind many choices, revealing the disempowering mechanisms often encoded within them”, which is to say that the choices you make in the games are built to have correct or incorrect paths, and actively or passively lecture you on which ones to choose. The game sheds light on this idea with the character of the narrator.

Sarian remarks that The Stanley Parable borrows many elements of the Theatre of the Absurd, a dramatical movement in the world of theatre which leaned heavily on themes of absurdity and existentialism. Typical plays would have very little plot and relied mainly on the interaction of the characters in seemingly meaningless situations. The plays would also be cyclical, meaning that they would end in the same situation as they started in, which is also present in The Stanley Parable. The essence of the Theatre of the Absurd is often surmised as being a riddle without an answer. This makes for an interesting setting for a game where the narrator sets the player a clear path of what to do.

The Stanley Parable is riddled with paradoxes. This is summarized best with the game’s numerous choices between two doors. If the player chooses the one the narrator says, the parable – the intended story – continues. If the player chooses the “wrong” option, triggers a different dialogue depending on which state of the game the player is in and how much he has “annoyed” the narrator. The paradoxes, however, lie in the fact that every action you take in the game has a path it will lead down on. There is no actual freedom because the game’s storylines are already written. Rebelling against the narrator is a part of the game and thus not actual rebellion.

The paradoxes are especially highlighted in the endings. The “freedom ending” is unlocked if the player obeys all the narrator’s orders and plays his part in the parable. Ironically, the player becomes Stanley themselves – pushing the buttons they are told to. The “museum ending” introduces a meta-narrator, who shows the player a museum exhibit in which the creation of the game is outlined and tells them “when every path you can walk has been created for you long in advance, death becomes meaningless.”. She then begs the player to quit the game as they’re being inched closer to death. The meta-narrator presents quitting as the only way to beat the game and pleads with the player to “not let them choose for you”. However, if the player was to quit the game, “they” would still be choosing for you.

The Stanley Parable leaves the player constantly questioning their next move but provides no answers or satisfactory endings. According to Sarian, this allows the player to reflect on themselves and on their role that they play as choosers within interactive narrative-based games. It highlights that choices do not make us free, and sometimes even limit us.

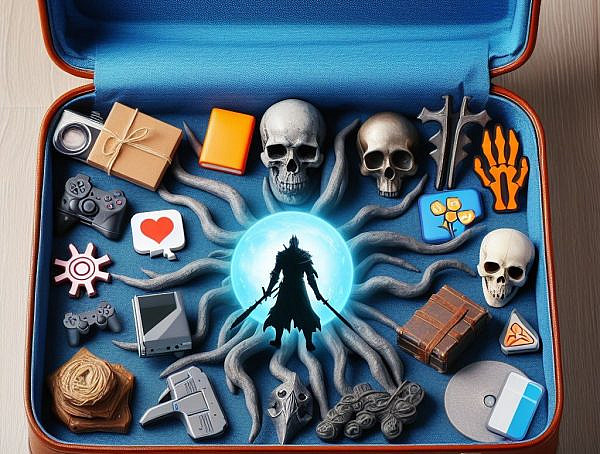

The image is taken from the game’s steam page.

You might also like

More from Game Research Highlights

How do you want to do this? – A look into the therapeutic uses of role-playing games

Can playing RPGs contribute positively to your wellbeing? A recent study aims to find out how RPGs are being used …

Eldritch horrors and tentacles – Defining what “Lovecraftian” is in games

H.P. Lovecrafts legacy lives today in the shared world of Cthulhu Mythos and its iconic monsters. Prema Arasu defines the …

Are Souls Games the Contemporary Myths?

Dom Ford’s Approaching FromSoftware’s Souls Games as Myth reveals the Souls series as a modern mythology where gods fall, desires …