The notion that digital games can be used beyond entertainment is an idea that is well accepted and caught on as a new genre by itself – Serious Games. That said, much of the serious games developed are designed to train concrete concepts or skills, from academic topics such as history and computer programming; to learning about energy awareness, and simulators on how to assemble a car power generator. In Barton et al’s (2016) research paper however, the authors explored the effectiveness of serious games promoting more abstract learning outcomes. Employing the scientific method, the authors designed Missing: The Final Secret, a serious game designed to alleviate biases and put it to the test.

Using interactive storytelling and exploration, Missing: The Final Secret addresses specifically 3 ways how our daily cognitive biases are formed, by using game design informed by current research and theory. The underlying method of mitigation is heavily based on Kahneman’s theory of dual-process systems of reasoning which proposes that people generally use two systems of reasoning when we make judgments System 1, which is based on intuition, automatic and reactive thinking; and System 2, which is characterized by logical reasoning and rational, rule-governed thinking. Within the game, the researchers attempt to bring into the player’s consciousness the types of biases they have and providing players with knowledge how to recognize these biases in their daily lives. The 3 types of biases game specifically targets are – anchoring bias, in which one particular piece of information is given excessive weight or “anchors” the decision-making process; representativeness heuristic, where a judgment is made based on “what feels right” rather than considering the statistical probability of something happening; and projection bias, which refers to the tendency to overestimate how similar other people are to ourselves.

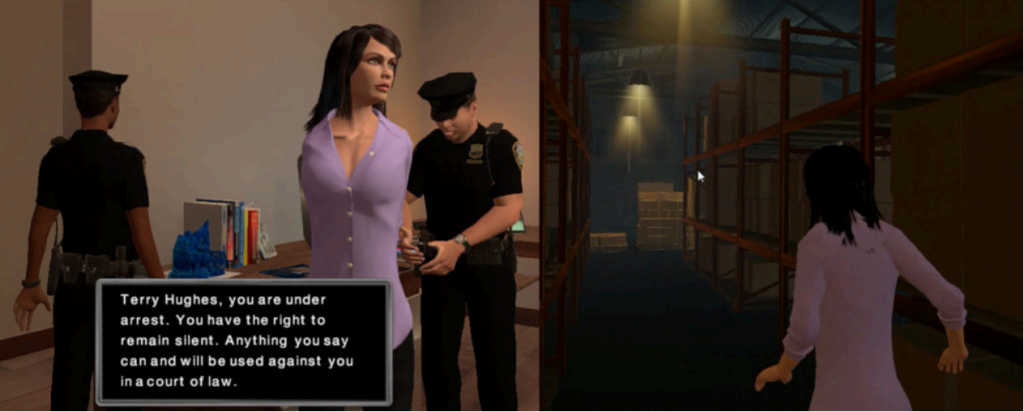

Over the course of 3 episodes, players interact with non-player characters (NPCs) and complete activities as they work toward solving the mystery driving the plot of the story. In each game episode, the player is exposed to bias-invoking situations, and their reaction towards these situations are evaluated. After the conclusion of each episode, an After Action Review (AAR) provides instruction on each of the three target biases, offers feedback on game performance, and provides practice examples for each bias. Using a framework that defines how what these biases are and how they are formed, the researchers came up with several methods to address these biases in-game.

Due to the overlapping causes in how biases are formed and the strategies can be applied to address them, the researchers were able to develop an efficient game that targets the origins of multiple biases at their common source and allows players to generalize their learning across multiple biases. In each of the game episodes, the learning process is incorporated directly into gameplay through four major phases: cognitive bias elicitation -> bias measurement -> participant feedback -> cognitive reinforcement. These steps are then repeated several times in each episode, offering a repeated learning experience.

For instance, in the first episode, an in-game character, Terry is celebrating the success of their news blog with the player. During the celebration, Terry proposes to the player the idea of expanding their business with a Facebook application, remarking that Facebook apps seem to be popular and that she spends around 30 hours per month browsing Facebook on her cell phone. In order to gauge whether or not that suggestion would be a valuable investment, Terry asks the player to estimate how often the average mobile Facebook user spends looking at Facebook. Based on the player’s response, the game assesses if the player is biased (by providing an answer similar to what Terry suggested as their experience with Facebook apps earlier in contrary to the actual answer). The player’s measured bias then serves as the basis for the feedback that the player will receive during the AAR for each episode.

In order to assess if serious games have long-term effectiveness compared to traditional methods, the researchers compared the bias recognition and mitigation of two groups – one who played the game, and the other who watched an educational control video on cognitive bias. Even after a 12 weeks gap, it was evident that the serious game was significantly more effective for teaching the mitigation of cognitive biases than the educational control video. In conclusion, employing relevant theory to guide the game design process is a promising approach for building serious games that teach an abstract topic.

Original Article: The Use of Theory in Designing a Serious Game for the Reduction of Cognitive Biases

(http://todigra.org/index.php/todigra/article/view/53/101)

You might also like

More from Game Research Highlights

How do you want to do this? – A look into the therapeutic uses of role-playing games

Can playing RPGs contribute positively to your wellbeing? A recent study aims to find out how RPGs are being used …

Eldritch horrors and tentacles – Defining what “Lovecraftian” is in games

H.P. Lovecrafts legacy lives today in the shared world of Cthulhu Mythos and its iconic monsters. Prema Arasu defines the …

Are Souls Games the Contemporary Myths?

Dom Ford’s Approaching FromSoftware’s Souls Games as Myth reveals the Souls series as a modern mythology where gods fall, desires …