Exploring the “indie” aesthetic, and what it means to be an independent developer.

Tommy Refenes, independent developer, seen here working on Super Meat Boy. Screencap from Indie Game: The Movie (2012)

Over the last decade of game development, the independent games scene, or “indies” as they are colloquially known, has arisen as a powerful creative force in the games industry, serving as a counterpoint to big-budget “triple-A” games. But a term as popular and widely used as “indie” demands classification and clarification to truly understand the root of the indie phenomenon, even though it seems to be on the wane already. To this end, the authors of the paper, Maria B. Garda and Paweł Grabarczyk have taken the effort to dissect the meaning of the term to clarify what it means to be both independent and “indie” in the greater context of the gaming industry, and design and aesthetic aspects that unify certain independent games.

For starters, to be independent automatically assumes a kind of typical relationship in games development, which is commonplace within developer-publisher relations in the industry. For years the game development model has revolved around those publishers financing and publishing the developer’s projects, while also asserting creative control by dictating how their money is used. An “independent game”, therefore, breaks away from this model in one or more of three following ways: It can be self-funded, as many indie projects are, which in turn places practical constraints on their scope. It can also be creatively independent, as the developers are free of any kinds of mandates put upon them by publishers and create the game for themselves, and it can also be independently published. For a game to be independent in some respect, it can have any one of these qualities, but there is a lot of wiggle room: For example, the Metal Gear Solid franchise can be considered creatively independent, as the series has been until recently overseen largely by auteur game developer Hideo Kojima while also enjoying the financial backing and publishing of a large publisher like Konami without much intervention..

The aforementioned three qualities are of course only extrinsic ones, and do not explicitly affect the outcome of the final product: Indeed, Garda and Grabarczyk argue as a thought experiment that a game like Super Meat Boy could very well have been a commercial “triple-A” game merely masquerading as an independent one, if its development and roots weren’t already well documented in Indie Game: The Movie. Games like Valiant Hearts straddle that line of evoking an indie game aesthetic, despite having the backing of a large company like Ubisoft behind it. Similarly, we can look at shareware games from the 1990s that were produced by small teams and distributed freely though systems like bulletin boards and the early Internet. These shareware creations, created by small teams of what we used to call “bedroom programmers” seem to fit the bill of an independent game, yet we would be hard-pressed to call them “indies” as we now understand the term.

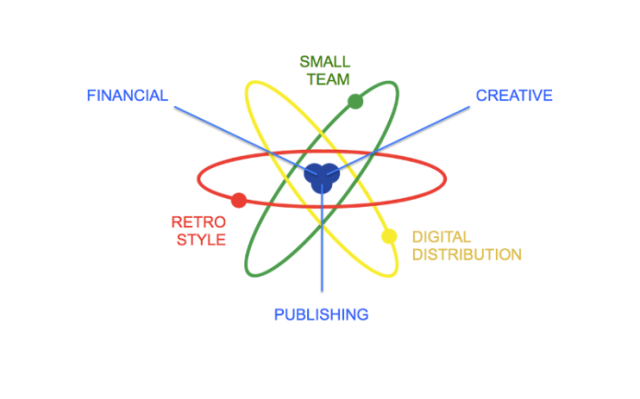

To wit, the authors present a model of the “indie” game aesthetic, which essentially emerged wholesale in the mid-2000s with the rise of digital download services and the formation of the Independent Games Festival. At the core of the model are the aforementioned extrinsic criteria, which usually follow into intrinsic results that form together into the “indie” aesthetic: Because these games are created on small budgets by small teams, they usually sport a distinctly retro aesthetic, reminiscent of older games similarly made by small teams for smaller budgets, or other games made with freely available tools. “Indie” games are usually smaller in scale as well for the same reasons, and because of their financial and creative independence are allowed to explore new gameplay conceits as well as genres that have fallen out of favor in the mainstream, such as 2D platformers. Their smaller size was also a boon for digital distribution, allowing their games to be easily downloaded online, though this advantage has diminished over time. Best of all, with the low-risk and low cost of digital downloads, these indie games can directly target niche markets. Finally, there is a strong community of indie developers, with a common mindset based on providing something that the mass market does not.

All in all, the duality presented here helps further define the scope of “indie” game development, both as a contrast to mainstream games, as well as defining their time and place apart from both the past and the future of “independent” development.

Original article: http://gamestudies.org/1601/articles/gardagrabarczyk

Authors: Maria B. Garda & Paweł Grabarczyk

Published in: Game Studies, vol. 16 no. 1, October 2016

You might also like

More from Game Research Highlights

How do you want to do this? – A look into the therapeutic uses of role-playing games

Can playing RPGs contribute positively to your wellbeing? A recent study aims to find out how RPGs are being used …

Eldritch horrors and tentacles – Defining what “Lovecraftian” is in games

H.P. Lovecrafts legacy lives today in the shared world of Cthulhu Mythos and its iconic monsters. Prema Arasu defines the …

Are Souls Games the Contemporary Myths?

Dom Ford’s Approaching FromSoftware’s Souls Games as Myth reveals the Souls series as a modern mythology where gods fall, desires …