The ability to navigate different spheres of reality could explain why we enjoy – and learn how to master – virtual worlds

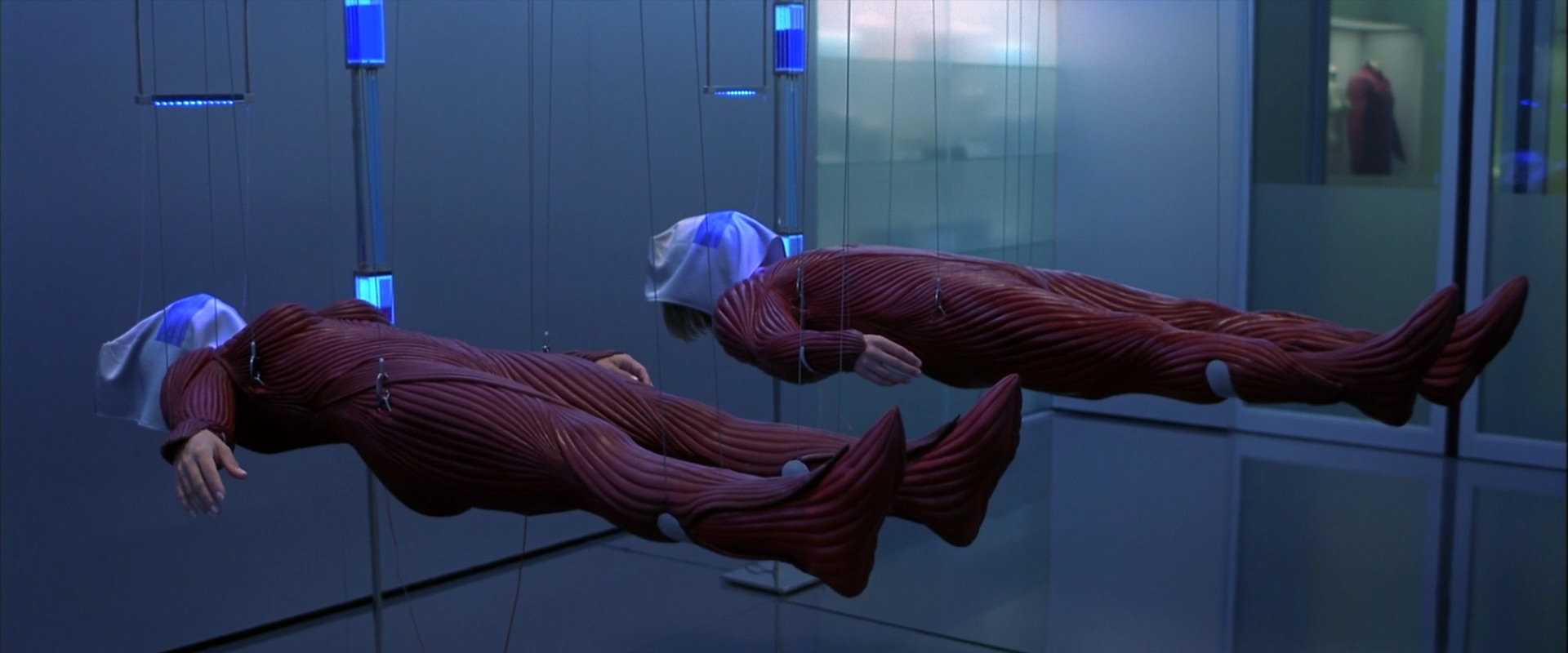

What is real and what is a dream? What actually differentiates them? These questions have been explored thematically in various fictions across different media. You may know the theme from popular culture and films such as Inception or The Cell, where the main characters navigate different spheres of reality. The authors of “Meta-Literacy in Gameworlds” compare the previously mentioned phenomenon to that of a player navigating different spheres of reality in a gameworld. This is also known as “meta-literacy”.

Meta-literacy is relevant for understanding why we like to spend time not only in gameworlds, but virtual worlds of all types. Meta is a Greek prefix originally used to indicate changes in a position or a state, or for things that went “beyond” or “through”. Take, for instance, the word “metaphor”, which literally means “carrying over”. It wasn’t until the 1900’s, however, that meta was used as we understand it today when linguist and literary scholar Roman Jakobson came up with the notion that “metalingual” is a function of language that allows it to talk about itself. In a sense, meta can be used for works of fiction which refer to themselves, to the conventions of their respective genres or their surrounding texts/commentaries. This also applies on games, and players have an ability to decode it through “meta-literacy”.

Through meta-literacy, the player crosses boundaries between reality and the game. The same occurs within the game, between the boundaries of fiction and game elements, or “the fictional level” and “the ludic level”. While the fictional level covers everything related to story and narration, the ludic level relates to the game itself. The former concerns aspects like characters, themes and genre, while the latter entails aspects of rules, goals and mechanics. A meta-literate player can re-create a bridge between the real, the ludic and the fictional. In essence, the crossing of boundaries is about the player making sense of the game and its relation to the real world. At the core of re-creation is the ability to use previous knowledge and experiences. For example, in order for a parody to have an effect on the audience, the audience needs knowledge of the genre being made fun of. As illustrated here, then, meta-literacy is dependent on how an audience experiences and engages with gameworlds. In turn, this affects the audience’s ability to traverse the boundaries between the real, the fictional and the ludic.

Games are meta in two ways: they are both cultural/representational (like literature and films) as well as ludic. What makes video games exclusive, however, are the playful experiences they provide through both story and game elements. Meta in a game occurs when fiction refers to itself, conventions of their genres or other commentary about games. A game can either be self-referential or intertextual, referring to other media artefacts or commentaries. Thus, a game can refer to something about itself or outside of itself.

Consider “idle animations” in an action game, for example. The player character taps the ground with their feet, glaring at us, as if to say: “stop wasting my time”. Here, he is pointing at the ludic level from inside the fictional level while requesting an action from us as both spectators and ludic actors. This means we are on a ludic and fictional level at the same time. This case illustrates the different levels of fiction, game and reality that we, as players, are navigating between.

Another case that demonstrates meta-aesthetics is when games refer to themselves by parodying their own genre. In the RPG game Icewind Dale II, two NPCs challenge you to a contest where you are asked to use your bow for destroying a keg far away from you. “There’s a barrel atop of the wall just to the north of us”, one of them says. “You might not be able to see it… with that strange fog that comes up, but it’s there”. The comment refers to the exploration system of the game. Every place your party has not explored is covered in black on the map to represent “unknown territory”. The black layer will progressively vanish as you journey through previously unexplored areas. Similarly, explored areas will be covered in fog when you venture further away from these areas. This indicates you are too far away from these areas to retrieve real-time information about them. The exploration mechanic described here resembles the genre convention of real-time strategy games. As a piece of information this is crucial for interpreting the NPC’s comment.

Some games, especially in the real-time strategy genre, have been known to use “fog” as part of their exploration mechanics.

This comment on the “strange”, progressively appearing “fog”, can be interpreted as an in-joke addressing the lack of logic of the fog on a fictional level. However, the exploration system as a game mechanic makes perfect sense in terms of certain genre conventions. If the comment works as a subtle invitation to share an in-joke with others, the player may feel privileged, in a sense. The authors of the article suggest, in other words, that being meta-literate could add an extra thrill to reading/watching when taking part in being knowledgeable of a hidden or subtle reference.

In conclusion, the authors argue meta-literacy is about having a sense of being in the gameworld while being aware of things external to it. Meta-literacy does not disrupt the gameplay experience – we can be engrossed in playing games while being aware of the references they make, in addition to being aware of our own experiences. Crossing boundaries between the real, fictional and ludic as well as making sense of these levels helps the player, ideally, in mastering the gameworld. Understanding references of the fictional and the ludic carries a pleasure of discovery but also of recognition and bodily experiences of play as we revive memories of mediated experiences and real life. In short, meta-literacy explains partly why we enjoy inhabiting gameworlds and virtual worlds of different kinds – and why we spend so much time in them.

The original article “Meta-Literacy in Gameworlds” (2016) by Silviano Carrasco and Susana Tosca can be found here.

You might also like

More from Game Research Highlights

How do you want to do this? – A look into the therapeutic uses of role-playing games

Can playing RPGs contribute positively to your wellbeing? A recent study aims to find out how RPGs are being used …

Eldritch horrors and tentacles – Defining what “Lovecraftian” is in games

H.P. Lovecrafts legacy lives today in the shared world of Cthulhu Mythos and its iconic monsters. Prema Arasu defines the …

Are Souls Games the Contemporary Myths?

Dom Ford’s Approaching FromSoftware’s Souls Games as Myth reveals the Souls series as a modern mythology where gods fall, desires …