Observer connects with the player on an uncomfortable meta-level. But does that really suit a video game?

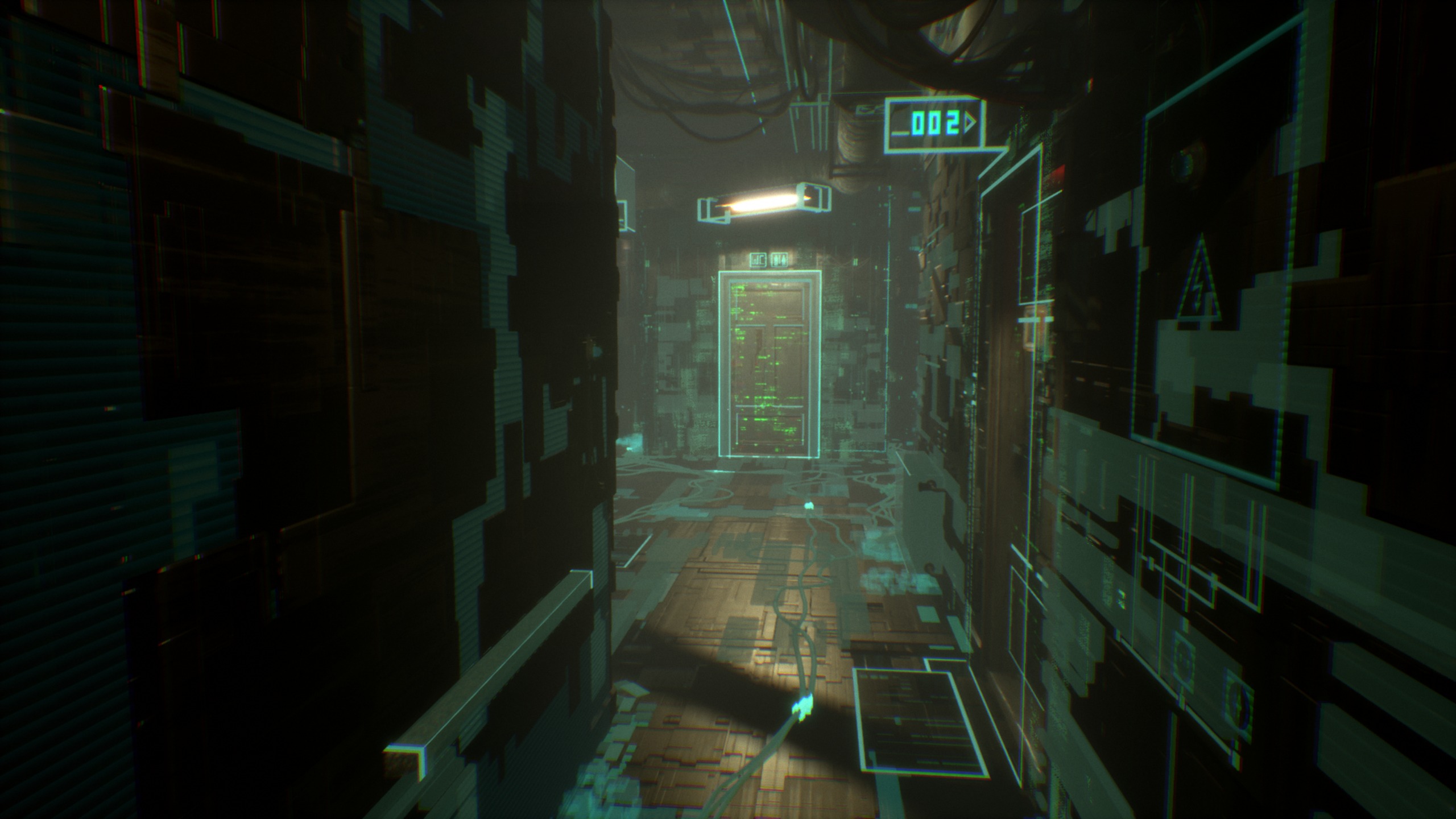

I played Observer a while ago. I crawled through its cyberpunk hellscape in a few sessions with some friends, and it was quite a ride to say the least. Having no experience with Layers of Fear, the previous game from Observer’s developers Bloober Team, I went into the game with zero expectations – save for the general cyberpunk aesthetic of 2084 Krakow. It turns out Observer was not a great game per se, but rather an interesting yet often unpleasant experience.

The game revolves around Daniel Lazarski, an observer – a government detective tasked with diving into the minds of people unwilling or unable to share critical information. Throughout Observer, he travels through various subconscious environments inside the minds of Krakow’s mentally scarred denizens. Outside these surreal sequences, the game incorporates Condemned-like investigation with different vision modes for scanning the crime scenes. Both are made possible with cybernetic enhancements – a part of daily life for Daniel and most of the world around him.

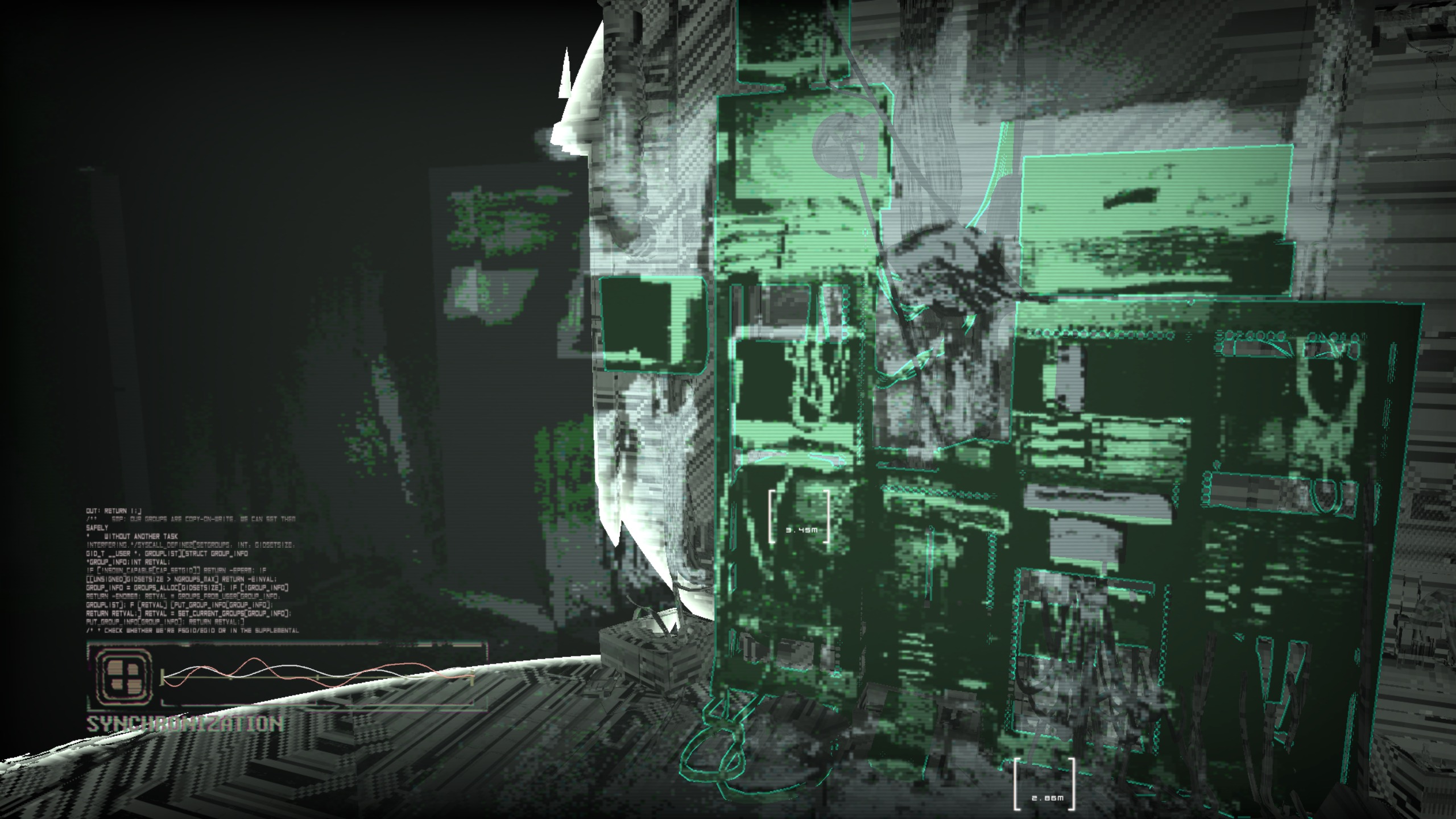

All this takes a toll on our gruff protagonist. Mind-diving and using the vision modes is very taxing to the mind and the body, and the symptoms manifest as visual static, among other cues. As a result, Daniel is dependent on synchrozine, a drug that dampens the drawbacks of the enhancements. To keep these side-effects at bay, he needs to take one pill after another on a regular basis.

Aside from the side-effects themselves, just using the cybernetics is already visually quite exhausting. Two of the three vision modes scan the environment every few seconds, distorting and wobbling the screen temporarily each time. The vision modes are also draining to look at even without the scanning, especially with the pixelation effect in the electronics-focused EM mode. This, coupled with the different psychedelic landscapes explored through other people’s minds, made playing Observer feel like a marathon for the eyes.

Near the end of our playthrough, we had an intriguing realization: we, as players, were just as addicted to the synchrozine pills as Daniel. We didn’t pay attention to the effects of the game’s visuals until we had already played through a large portion of it, but at that point they were very tangible. My head ached almost constantly, and I felt physically ill in ways I never had while playing a video game. This was, to varying degrees, true for everyone present (although, playing the game with a video projector and a big screen might’ve been a factor). We essentially craved the synchrozine beyond the fourth wall. This created a meta-level of sorts in the game – especially because, in a way, we were ourselves diving into Daniel’s head. Taking the pills had an unpleasant temporary motion blur effect as well, but it was only a minor problem in comparison.

Besides being an interesting meta-experience and a unique commentary on addiction, this discomfort also exemplifies an interesting conflict: the value of an artistic statement against the enjoyment of players. I can’t help thinking that all this meta-content may very well have been intentional, but as a game, Observer stopped being an enjoyable experience largely due to the actual, real, physical discomfort.

This discussion ties in with the question of “are games art”, because in art, a statement made is often valued more than the audience enjoying the piece. If games are not art, and are instead considered entertainment, shouldn’t they be primarily enjoyable? If games are art, how does interactivity fit in here – the player needs to be motivated to play the game to its end, right? That is, unless quitting the game prematurely is in itself a valid, perhaps even “canon” experience. This is sometimes said about Dark Souls. Then again, there are also things like interactive art installations without a definitive end goal for the audience to reach or progress through.

How about gamified experiences that are unpleasant or painful by definition – how do they relate to the “art or entertainment” question? More specifically, how do they relate to the role enjoyment plays in entertainment? Things like the PainStation, a twisted version of Pong that inflicts real pain on its players. A time I played Trivial Pursuit with extra rules involving an electronic shock roulette machine. Hell, even BDSM! Art or not? Enjoyable or not? The answer and its implications most likely depend on the person answering the question.

I won’t try to give any answers here, since even just scratching the surface would be subjective at best. But perhaps playing Observer really was worth it, despite actual “fun” being far from it in the end. After all, it sparked this whole thought process and remains an experience that I’m glad I had.

——————–

Platforms: Windows, PlayStation 4, Xbox One, Linux, macOS, Nintendo Switch

Developer: Bloober Team

Publisher: Aspyr

Release Date: 15 August 2017

PEGI Rating: 16

You might also like

More from Features

Game Awards – Celebration of talent or a Marketing Extravaganza?

The Game Awards 2024 is over and the winners are announced. However, are they still following the same pattern that …

Worlds in a Finnish Theater: League Finals, Community, and Döner Kebab

I travelled to Helsinki to watch League finals in a cinema, and it was worth it. #leagueoflegends #esports #community #worldfinals