#Frostpunk and sweet #totalitarianism?

I recently finished my first playthrough of Frostpunk, a new city-building survival game by 11-bit Studios, the developer of This War of Mine, also a survival and strategy game. As is the case with This War of Mine, gameplay is highly focused on resource management in Frostpunk. As a mayor, the player character starts out with a small group of survivors, workers and engineers, as well as small caches of supply for building the city. The game is set in a completely frozen world and one of the ultimate challenges is surviving the great storm. In the meantime, the player manages the level of discontent and hope of citizens in what constitutes a democracy through, for example, establishing laws. If not properly managed, the level of hope and discontent may threaten the productivity of society and the rule of the mayor.

Frostpunk is not merely a city-building game, but also a survival game. While resource management is at the core of gameplay, social aspects are an important part of it and helps construct a story around the mechanics, rules and goals. This makes the city feel very much alive when the player faces crucial ideological decisions about whether to implement democratic or totalitarian tendencies. The experience of totalitarian rule became very concrete to me by the end of the game. The Londoners, a rebel group in the city, started stirring unrest amongst the civilians that made them gather on the streets and seek up what I, as a mayor, perceived as false prophets.

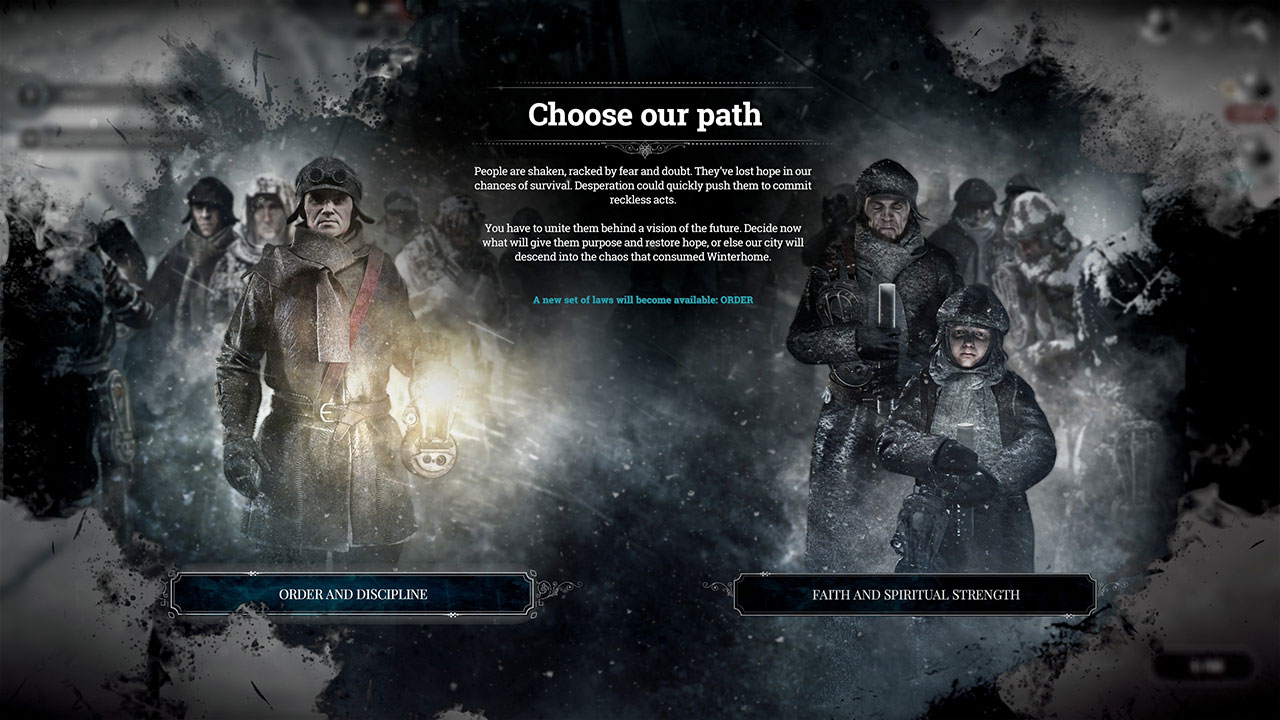

As a mayor, I had entertained the idea of totalitarian rule as one of my last resorts to manage resources and technological advancement successfully. I desperately wanted to complete the game. For this, I needed the city to grow. The biggest threat were potential rebels and their recruitment of ordinary citizens to join their group intending to abandon the city. I couldn’t afford to lose my workforce. So I had the choice to impose order and discipline or faith and spiritual strength. While both ideologies are used to give citizens a sense of purpose (which ultimately affects the level of hope and discontent) they afford the player different sets of laws for managing the city, all totalitarian in nature.

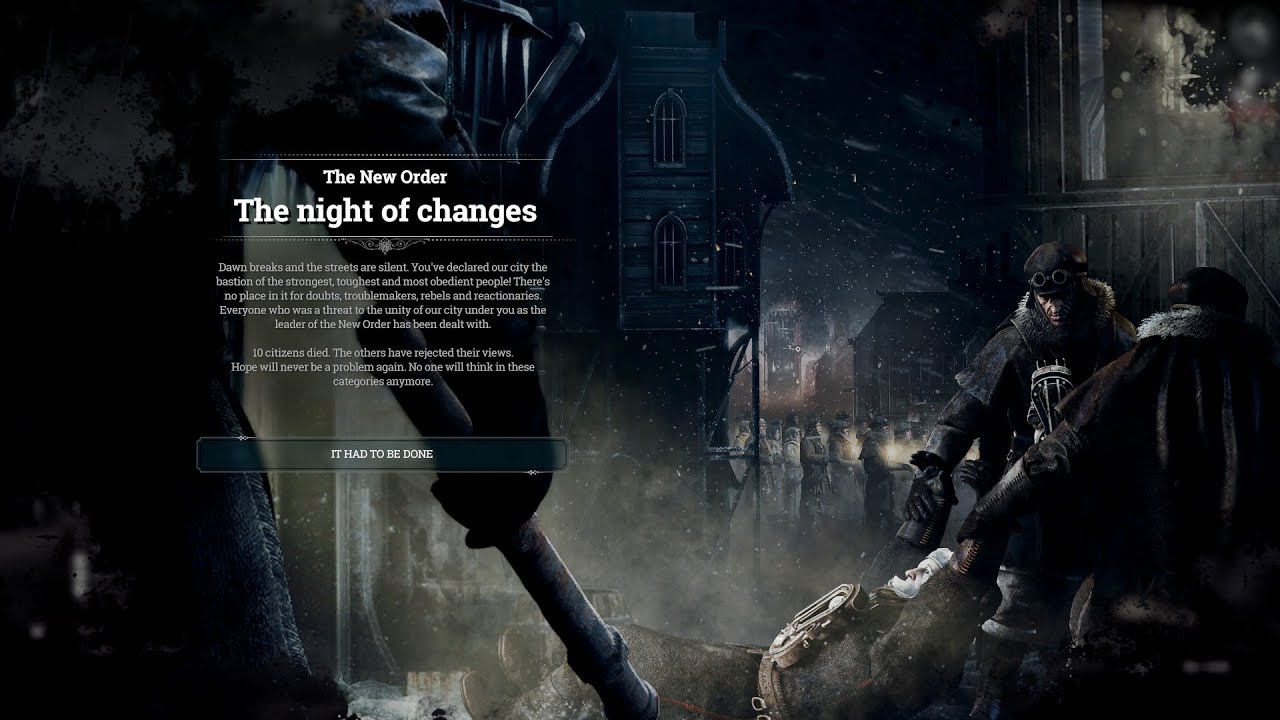

The path I chose was order and discipline. It introduced a new game mode for establishing laws that allow new systems of control and surveillance like a neighbourhood watch, guard stations and enforced morning gatherings. The difficulty level of the city simulation still felt overwhelming. So, I decided to implement what I felt was ultimate totalitarianism – a “New Order” – where citizens’ hope would never be a problem again. The consequence for gameplay was that none of my actions affected the hope of citizens. Hope became self-evident, as something taken for granted as I did not have to think about the consequences of my actions in terms of hope. Imposing this type of totalitarianism on this society felt like a relief. It was surprisingly easy. And the small rebel group of Londoners were gone.

Regardless of the developers’ intent, the ease at which totalitarianism could be implemented calls for some reflection on why it felt so necessary to implement an “ultimate” totalitarianism. There is something strangely perverse in being rewarded with a compliant workforce when using laws to control levels of freedom in the game, yet this is reflected in societies both past and present.

In game studies, this relation between game and real life can be analysed through the so-called “v-effect”. The v-effect is the formal means through which cultural expressions like games draw attention to naturalised contradictions – such as the way ideologies develop in societies – by making them strange. To the player, this “strangeness” becomes concrete in how the game simulates real life, and may feel very alienating. The concept of v-effect originates in literature and drama studies which have discussed how art (as cultural expressions) can refresh our senses by challenging us as readers and spectators so that we do not only recognise, but truly see the world around us. This can be applied on understanding the way games operate.

Thus, the v-effect is a device for de-familiarisation, and has been used to convey knowledge that affords critical reflection and political mobilisation. Making ideological decisions in my playthrough felt empowering. This is because of the way management of citizens hopes and discontent can develop into tendencies where you will try to control these sentiments to advance a society and its technologies as part of the game’s goal. My main argument is that this experience may be deeply alienating if you, in real life, are in the position of being a strong advocate democracy and civil rights.

The game, however, made me aware of sentiments inherent in the power dynamics and ruling class of democratic and totalitarian states. This is one of the reason I find Frostpunk, at its best, is political in the way it shows you the process of how societies with democratic or totalitarian tendencies may develop. In practice, however, this means the game is just one possible world and a simulation of how these tendencies could be shaped. What may be unique about the game experience, then, is how it makes you live through these tendencies being shaped.

Game: Frostpunk

Developer & Publisher: 11-bit Studios

Release date: 24.4. 2018

Platform: PC