Naval units featured in the launch trailer of Civilization V: Gods & Kings. (Source)

Dom Ford intersects game studies with postcolonial theory, or postcolonialism, an academic discipline concerned with colonialism and imperialism: countries acquiring, establishing, maintaining, expanding and exploiting controlled remote territories, or colonies for short. In his journal article recently published in Game Studies, Ford examines the popular strategy game Sid Meier’s Civilization V from the perspectives of postcolonialism.

Civilization V is often applauded for its educational capabilities and presented as a strategy game during which neutral, albeit simplified, accounts about the societal progression of different human civilizations emerge. Ford’s main argument is that studying the game from the perspectives of postcolonial theory reveals the game’s problematic, inherently homogenized imperialist narrative that silences histories of non-colonial societies and insists on a Western-centric notion of history.

“I am Chief Pocatello of the Shoshone, what brings you to the lands of my people?“ (Source)

The article introduces the game and the respective video game genre of 4X strategy, defined by their four core elements of exploration, expansion, exploitation & extermination. What follows is a thorough case study of Civilization V where Ford reviews postcolonial literature, analyzes the game’s representations of technological progress, critically evaluates the exploration mechanic, and discusses the role of the player as well as the role of the game in educational settings.

The article applies concepts mainly from two postcolonial theorists, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak and Michel-Rolph Trouillot. Trouillot is concerned with the writing of history and what stories there get emphasized and silenced. Spivak describes voices suppressed by structures unable to hear them, and argues that failing to recognize one’s own ideological frameworks leads to generalizations. Their perspectives are utilized throughout the article.

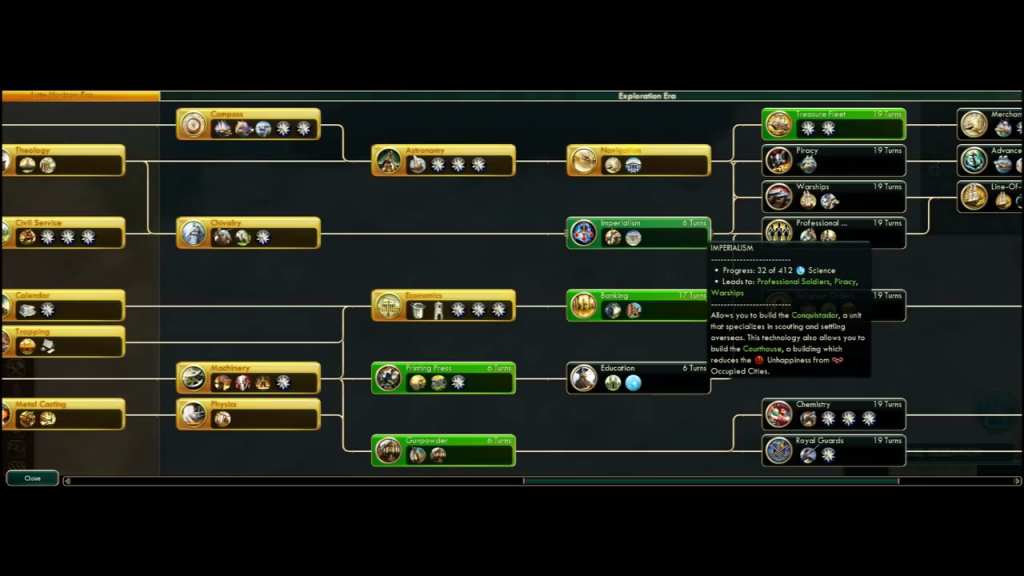

Imperialism as a researchable technology in Civilization V’s tech tree. (Source)

Civilization V’s tech tree is a flowchart representation of a society’s technological progression. The restricting linear nature hints at technological determinism, a reductionist theory where societal and cultural development is solely driven by technology, and suggests a homogenic course of causal relations. Meanwhile, societies emerging at different times in history are disregarded.

Scientific Victory is about winning a version of the Cold War space race. (Source)

Exploration might seem like harmless observation, but Ford points out that it is ultimately conducted not as an act of curiosity, but to gain access to strategic resources and information. The game’s fog of war calls to explore, which makes it possible to expand to new areas, exploit the revealed resources and exterminate opposing forces.

Through these examples, it becomes apparent that the product has imperialist undertones, but what is the role of the player in acting out this narrative? The interests of players are different from the interests of social critics. Having played over 200 hours of Civilization V, Ford asks how the process of rehearsing the Western imperialist narrative through playing the 4X game is problematic, and turns to affect theory for answers. Anna Gibbs describes how we construct meaning from fictional narratives, which in turn affects our attitudes and ideas. Diane Carr however seems sceptical of this, arguing that players detach the game world rules from those in the outside world upon entering and exiting the game’s “magic circle”, a conceptual field in games where players submit to following norms different from everyday life. Even so, the players are bound to the game mechanics and as such can’t win without employing the logics of empire structures. Civilization V is a grand story of imperialism that rejects competing narratives or even nuances like class or gender issues.

Conquistadors attacking the Mayan city of Palenque. (Source)

The game features generic barbarians, hostile tribes with no history or ethnic identity that solely exist to be conquered. A student playing the game might learn what barbarians are, but might also receive the dehumanizing colonial ideology that surrounds in-game barbarians. Adam Chapman calls for educated treatment, stating that historical games should be thought of as subjective, biased stories guided by ideology, similar to how actual historians treat histories. The article ends with reflections about the game’s Western world conceptions of territory and land ownership, and closing remarks suggesting that, for using Civilization V as an educational tool, a similarly critical reflection of the game’s embedded structures for students is recommended.

Sid Meier’s Civilization V. (Source)

Article: “eXplore, eXpand, eXploit, eXterminate”: Affective Writing of Postcolonial History and Education in Civilization V

Author: Dom Ford, MA in English Literary Studies, University of Exeter

Publication: Game Studies, volume 16, issue 2

Published: December 2016

Language: English

Online: http://gamestudies.org/1602/articles/ford

You might also like

More from Game Research Highlights

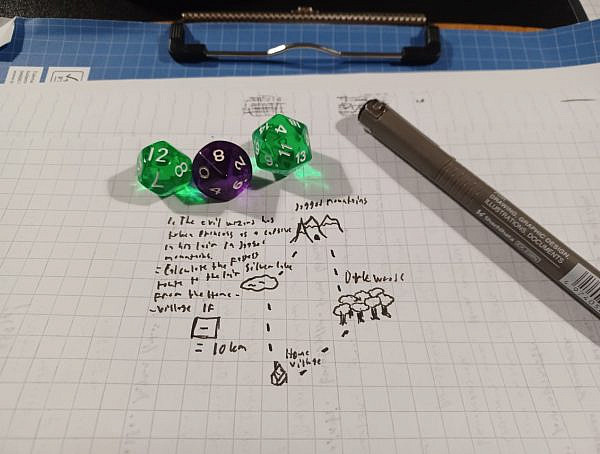

How do you want to do this? – A look into the therapeutic uses of role-playing games

Can playing RPGs contribute positively to your wellbeing? A recent study aims to find out how RPGs are being used …

Eldritch horrors and tentacles – Defining what “Lovecraftian” is in games

H.P. Lovecrafts legacy lives today in the shared world of Cthulhu Mythos and its iconic monsters. Prema Arasu defines the …

Are Souls Games the Contemporary Myths?

Dom Ford’s Approaching FromSoftware’s Souls Games as Myth reveals the Souls series as a modern mythology where gods fall, desires …