How do fan-made archives of a game series’ texts relate to the official titles? Dennis Jansen’s article explains that deciding on canonicality in a fictional universe is no simple task.

In his article “A Universe Divided: Texts vs. Games in The Elder Scrolls”, Dennis Jansen details the role of online fan-made archives in a canonical conflict between The Elder Scrolls games and texts. Jansen focuses mainly on a website called The Imperial Library and a fan phenomenon called the “archontic fandom”.

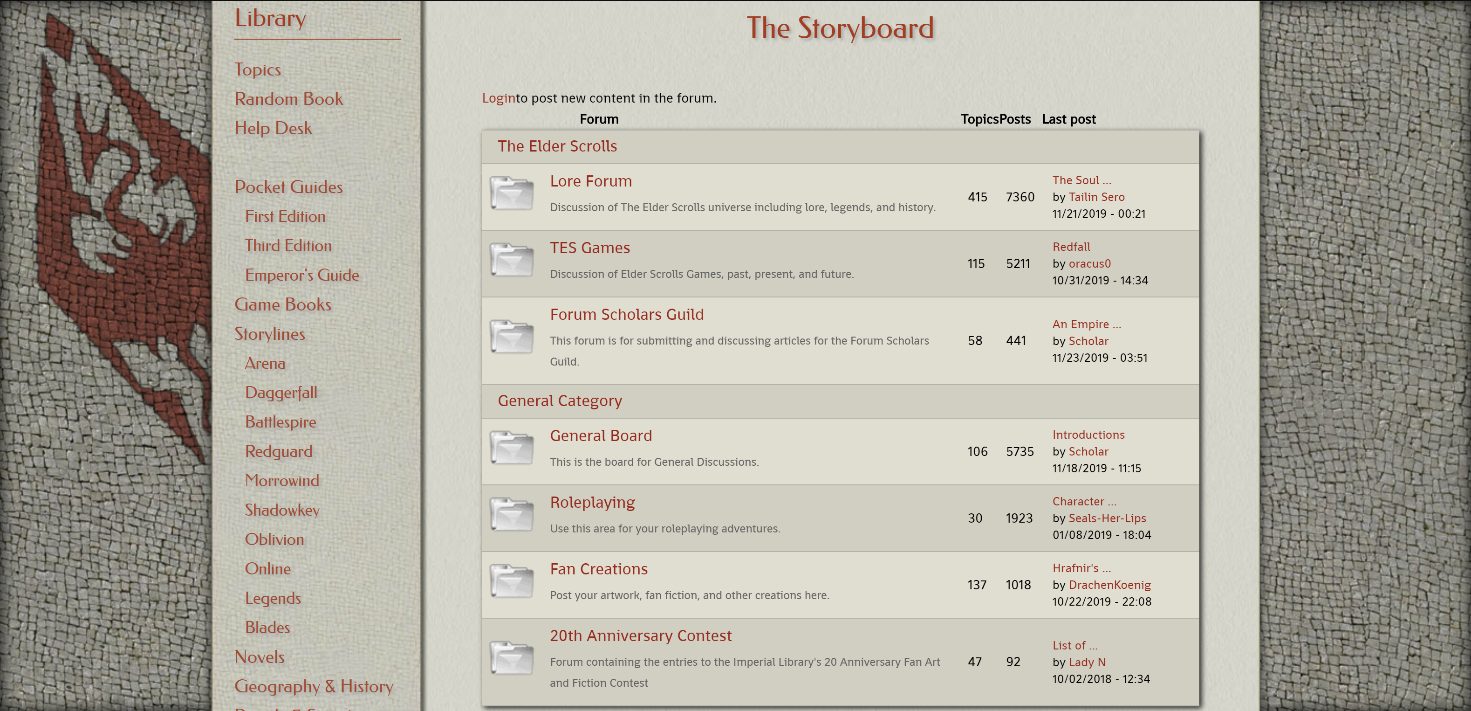

The Imperial Library is an archive containing a vast mass of texts in, and about, The Elder Scrolls fiction. Its contents range from encyclopedic information on entities in the games to descriptions of the games’ main storylines, as well as nearly all of in-game and out-of-game books. Gathered from multiple different sources, these texts describe the large and convoluted The Elder Scrolls narrative universe.

Jansen uses the term “narrative universe” for multiple reasons. First, it communicates that most of the worldbuilding information is never seen or encountered directly. Second, it represents the construction of fiction that “extends beyond the immediate setting of the story being told at any given time – the “immediate setting” here refers to the story events that explicitly take place at the current moment.

The author continues that The Elder Scrolls universe is an extremely complex one, with its many games and other media made by different teams at different times. As a result, the worldbuilding often contradicts itself to the point where it’s difficult to distinguish canonical information from non-canonical information. To solve this, fans of the narrative universe have opted to collectively judge what information should be archived and considered canon – a phenomenon Jansen calls the archontic fandom.

Coined by Matt Hills – and partly influenced by Derridean views on an archivist’s right to both create an archive and to decide what is worthy of inclusion – the term “archontic fandom” describes a fandom that seeks to understand a fictional universe by archiving relevant, non-context-dependent information from the source material. This type of fandom, accordingly, decides what material should be considered canon and, on the other hand, what should be rejected from the archive. In the case of The Elder Scrolls, Jansen highlights a tendency among many fans to prioritize the in-game and out-of-game texts over the games themselves. The fans essentially view the games’ authority on the fiction as less valid. He also notes that this kind of an archive-based view differs from a linear understanding of a narrative: it favors a more interconnected web of texts that is updated constantly.

Jansen specifically describes these sorts of archives as paratextual. This means that the most relevant archived texts are surrounded by other related texts that provide additional information and guide the reader’s interpretation of the main text. This kind of an archive also functions as a paratext of its own in relation to its corpus of lore-relevant texts. This is because its varying amounts of tags and other meta-information provide additional context, organize the content in specific ways, and guide the reader in their own right.

Jansen found that The Imperial Library’s contributors have difficulties deciding on the canonical status of borderline texts, such as forum roleplays involving the developers. These sorts of texts are heavily disclaimed, contested, and placed in less visible locations in the archive. At the same time, such texts may still be used as paratexts to support other texts. The scope of fans’ views on accepted canonical material varies greatly: some are more lenient, some only accept material by the original developer company, and some outright question all material outside the games.

The author also raises an issue with the fans prioritizing texts over the games: the games can exist without the texts, but not vice versa. This is because the texts need to be accessed through the games, and because the games are what originally gave the texts their context. According to Jansen, however, the existence of fan-made archives counters this, because they allow the texts to be accessed without the games – making the texts stand on their own.

At the end of the article, Jansen addresses a divide between fans’ views on the prioritization of The Elder Scrolls games versus texts. He explains that that even though many fans see the games as abstractions that can never represent the fictional universe as accurately as the texts, other fans disagree with this and instead regard the games as the priority over the texts. These game-prioritizing fans see the fiction brought to life by the games as a more concrete and valid representation of The Elder Scrolls universe. Jansen concludes by remarking that despite their differences, both views seek to understand the narrative universe through some sort of a hierarchical structure.

Original article: A Universe Divided: Texts vs. Games in The Elder Scrolls

Author and institution: Dennis Jansen, Utrecht University

Publication: Proceedings of Nordic DiGRA 2018

Published: November 2018

Online: http://www.digra.org/wp-content/uploads/digital-library/DiGRA_Nordic_2018_paper_12.pdf

You might also like

More from Game Research Highlights

Eldritch horrors and tentacles – Defining what “Lovecraftian” is in games

H.P. Lovecrafts legacy lives today in the shared world of Cthulhu Mythos and its iconic monsters. Prema Arasu defines the …

Are Souls Games the Contemporary Myths?

Dom Ford’s Approaching FromSoftware’s Souls Games as Myth reveals the Souls series as a modern mythology where gods fall, desires …

Of claws and cuddles: Exploring Dark Cozy Games

Cute, wholesome, safe....dark, heavy, violent? Let's talk about dark cozy games!