Fan fiction, or the creation of original fiction based on an existing property, is a familiar concept to most people who have interacted with fandoms in any capacity. Fans belonging to marginalized groups within their fandoms often use fan fiction and other fan creations to create representation for themselves within the context of their favored media: this includes representation, interpretation, and exploration of gender and sexuality, as is discussed in the article “”theyre all trans sharon”: Authoring Gender in Video Game Fan Fiction” by Brianna Dym, Jed Brubaker, and Casey Fiesler. By analyzing metadata from fan fiction stories, specifically their tags as provided by the tagging system on fan fiction website Archive Of Our Own, they argue that fan fiction authors recraft video game narratives to better fit in with current cultural nuances and suggest that developers can expand diversity in their games by deliberately leaving room for this kind of interpretation.

The study begins by describing the “curated folksonomy” of tags on Archive of Our Own: tags are curated and maintained by volunteers to make searching for stories containing specific content or themes easier. Stories are categorized by content, rating, and content warnings; additionally, authors can tag whichever elements of their story they feel help readers find their stories. However, freeform tags are also used by authors to provide commentary on their stories and describe what they consider significant about their content.

The methodology the authors used in narrowing down a selection of video game related fan fiction involved first using keywords related to non-cisgender (i.e. identities of individuals whose genders do not conform to the gender assigned to them at birth) and non-heterosexual identities; after this, the scope of the study was narrowed further to involve only non-cisgender identities by using information from the LGBTQ Game Archive and Queerly Represent Me. These were used to select fandoms that have source games that purposely engage with LGBTQ audiences, contained a substantial number of stories tagged with non-cisgender identities, and contained stories from multiple authors. All games selected were western, emphasize story or narrative arcs, and contain RPG elements. In addition to using keyword tags, tags were read by researchers to determine if they contained themes related to gender identity.

The authors identified three major ways of interacting with narratives and queerness in metadata: writers reconstructing gender identities to expand or reclaim narrative space, player character identities being rewritten to expand beyond binary gender, and writers using tags to respond to developers and design choices. All of these critique the representation or lack thereof of non-cisgender identities in video games. The study elaborates on various games and game series, f.ex. the Dragon Age series, Overwatch, and Dream Daddy: A Dad Dating Simulator, describing the LGBTQ-related content in each game and how each individual fandom creates content related to non-cisgender identities. The authors identify certain tendencies as being common to most or all fandoms, such as authors discussing their rationale for rewriting existing characters as non-cisgender or mentioning in tags that they write a certain character as non-cisgender when nothing in the story itself makes it explicit.

A common critique in tags involves the revision of player characters that can be either male or female into non-binary identities. If a game only allows for male or female player characters, Archive of Our Own is less likely to generate official, curated tags for other identities, forcing authors to use freeform tags to describe their characters. This leads to a lack of flexibility in the folksonomy that reflects the games the stories are based on.

Writers also use freeform tags to address an audience. Among these tags, the research found three trends: hyperbolic or sarcastic critique, an author personally relating to a character, and writers disclosing their own identities aligning with the characters they’re writing about. Hyperbolic critique can respond to heteronormativity in general, game studios in specific or, in some cases, express approval of a game. In general, the authors found that these conversational tags reflected positive response from fans when diverse characters are well-incorporated into stories, as well as encouragement of the creation of more queer content.

The authors conclude that fan fiction reflects a desire of a certain subset of fans to expand narrative spaces. The fandoms observed push the boundaries of diversity in games in various ways, reflecting a desire for both more diverse characters and leaving characters open to fan interpretation. Lastly, the authors suggest that research could be done into the readers of fan fiction as well as those who write it to explore how readers see themselves rewritten into narratives.

You might also like

More from Game Research Highlights

How do you want to do this? – A look into the therapeutic uses of role-playing games

Can playing RPGs contribute positively to your wellbeing? A recent study aims to find out how RPGs are being used …

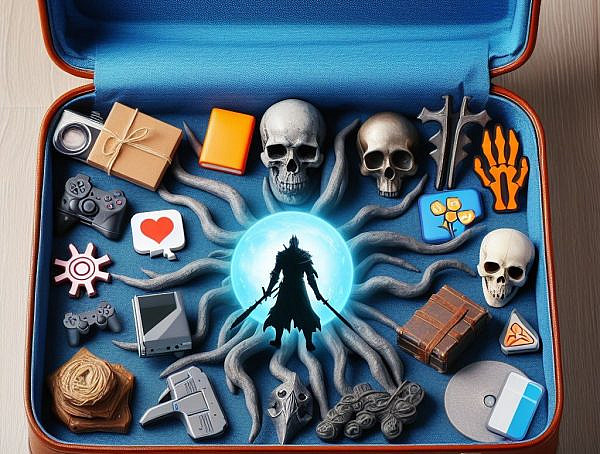

Eldritch horrors and tentacles – Defining what “Lovecraftian” is in games

H.P. Lovecrafts legacy lives today in the shared world of Cthulhu Mythos and its iconic monsters. Prema Arasu defines the …

Are Souls Games the Contemporary Myths?

Dom Ford’s Approaching FromSoftware’s Souls Games as Myth reveals the Souls series as a modern mythology where gods fall, desires …