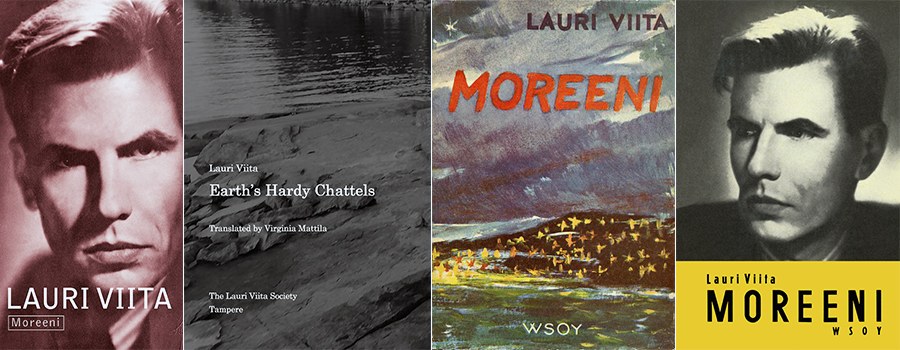

Tampere author Lauri Viita’s masterpiece Moreeni in English translated by Virginia Mattila

The translation was actually completed in the early 1990s, but was somehow forgotten and all but completely lost in a series of house moves etc. It was unearthed, a messy looking heap of papers, in 2015, at the totally unexpected request of Professor Harry Lönnroth.

It had been hoped to publish in December 2106, around the centenary of the birth of Lauri Viita (1916–1965), but the copyright formalities proved timetaking and tortuous and publication was only achieved in December 2020.

Hooked – from the very first page

A native of the North of England, Virginia Mattila recalls being totally hooked on reading the first two pages of Viita’s novel Moreeni, which came out in 1950.

Moreeni, meaning literally moraine, recounts events in and around the Nieminen family in Pispala in the early 20th century, including the building of the first modest dwellings there and the Finnish Civil War of 1918.

“I had read relatively little Finnish literature, and I am still no great literature enthusiast; I tend to read more history, especially social history. Fiction is really not my thing, but then, I have almost come to believe what happened in the novel,” says Virginia Mattila.

The novel is indeed a work of fiction, although it draws heavily on events in Viita’s own family. It was while regularly walking the selfsame route as the main character, Isaac Nieminen, from Finlayson’s cotton mill, where many of the figures in the book were employed, towards the cramped wooden working class homes of Amuri that Mattila began to fancy that it had all really happened.

“Isaac, trudging wearily homewards, noted the Factory School and the Factory Church and began to wonder if there might be a Factory Heaven and a Factory Hell – there’s the wit of the working man - and so I began to believe he was real”, she says.

All translated in the 1990s

Mattila began her translation in the 1990s, when her employment at the University of Tampere consisted of part-time teaching and translation on a no-work-no-pay basis. This left time to focus on translating Moreeni.

The work (340 pages) took roughly two years and she had an opportunity back then to read aloud a small part of it at an event in the University in the early 1990s.

“I can’t really remember when it was finished; I must have had a lot of language checking and other translation work by that time – and after all, I am not a literery type, nor have I any form in research or publishing.”

And so the translation just gathered dust for decades.

“There it was – all in an untidy heap somewhere. I retired nine years ago, and being a computer ignoremus, there was this old disc and a bagful of papers. The disc was somehow “lost to posterity”!

Unearthing all that paper

Somehow that ragged heap of paper survived a couple of house moves and sank over the years to the depths of a cupboard – to be miraculously resurrected when Professor Harry Lönnroth, engaged on an article on other Viita translations, suddenly called to ask Mattila about it.

“It had clearly suffered the ravages of time. Bits here and bits there, but there it was!”

Lönnroth had the papers scanned and invited a colleague, Professor Emeritus Gerald Porter, to take a look and comment.

“That was pretty important; he was my first and so far only reader and he was most encouraging. So, with some foreboding, I set to work on a cleanup operation,” Mattila remembers.

Professor Lönnroth approached WSOY and Lauri Viita’s heirs about publishing. Things went slowly. The Viita centenary came and went. Professor Lönnroth was able to ascertain that no other translation into English existed, only a couple of pages.

Virginia Mattila’s translation, Earth’s Hardy Chattels, was finally published in December 2020 by the Lauri Viita Society.

Mattila is grateful for Professor Lönnroth’s expertise, enthusiasm and persverance. Further valuable assistance came from Professor Emeritus Kaarle Nordenstreng in arranging for a layout faithful to the original physical appearance of the novel.

Moreeni has previously been translated into only five other languages: German 1964, Swedish 1965, Polish 1970, Hungarian 1977 and Russian 1981.

Will Viita be turning in his grave or rejoicing in Heaven?

Lauri Viita’s highly individual language and powerful mode of expression have been suggested to frighten translators off.

“That encouraged me. This was no commission allocated to me from outside but something I very much wanted to do,” says Virginia Mattila.

“It was a labour of love to attempt to do justice to Viita’s wonderful work. This was no business transaction”.

“I wonder if he is now turning in his grave or rejoicing in Heaven,” she speculates.

Moreeni abounds in vocabulary which is difficult even for Finnish readers. He made his own language and favoured word play. The dialogue is in a class of its own and one character has a speech defect. Plenty of work for the translator.

“I found myself running along the corridor at work to ask advice from the nearest Fenno-Ugrist or ask various other Finnish friends. Some of word plays went nicely into English, but not all of them.”

Mattila made a conscious choice to render the (low) social class of certain characters by using deviant grammar.

“The grammar is just plain wrong, but authentic. That’s what real people really use.” Mattila explains.

Mattila says that on the basis of spoken vowels it is easy for one English speaker to determine where in the country and where on the social ladder another English speaker comes from. But this cannot easily be committed to paper. So she stuck to bad grammar.

Mattila believes it likely that not all readers will go along with her choices.

In the translation the characters speak an ungrammatical vernacular which reflects their modest social status. An entertaining juxtaposition of modes of speech occurs when the simple mother, Joosefiina, is obliged to confront the superior teacher lady about the naughty drawing her son Kalle has made on a little classmate’s paper.

“Translating that scene was pure pleasure. Finnish has an apt expression for such ladies; in Finnish it would be hienopieru – translated best, I think, as ”a fine fart”. Finnish is great!

Iisakki became Isaac, but Joosefiina was retained

With the exception of Iisakki, anglicised to Isaac, the characters’ Finnish names are retained. Virginia Mattila opted for this change as in English eyes Iisakki looks pretty strange.

Although Viita is believed not to have seen Iisakki as the protagonist, to Mattila Isaac becomes one.

“To Finnish eyes Iisakki may look OK, but someone like Boris Johnson, say, would find it rather weird and I wanted to avoid that. Joosefiina and Oskari do not appear so; and they suggest a woman and a man. Paavali may be a little strange but occurs less frequently. Lempi does not look so odd, but I felt compelled to add ”whose name meant love”, Mattila recalls.

Names of places were problematic when occurring in word plays and rhymes. Joosefiina seeking flour (in Finnish jauho) in the village of Hauho was not successfully resolved.

Only at the very end did the title ”Earth’s Hardy Chattels” emerge. According to Yrjö Varpio, Viita used moreeni (in English moraine) to refer to both the celebrated gravel of the Pispala Ridge and the hardy folk, Earth’s hardy chattels (see page 2 of the text) who lived there. Mattila estimates that moraine is not a very common word in English and as a title would convey very little.

Isaac was initially a general handyman at the cotton mill, and later a carpenter and housebuilder. Describing his work involved a range of tools scarcely familiar to many modern Finns. An engineer friend of Mattila was kind enough to produce a model of a “holding hook” needed when building with logs. Visits to the Amuri Museum to see workers’ housing with communal kitchens and the outbuildings of a local farm were decidedly eye-opening.

Intriguing authenticity

Virginia Mattila was entranced and moved; the novel rang so true. At the beginning of the book Joosefiina’s old mother walked to Tampere through the summer night to deliver her aunt some boots. The aunt reprimanded the girl for wearing out her shoes unnecessarily on the long journey; nobody would have noticed and she could have walked barefoot.

“My old auntie born in 1910 had galoshes to go to school in, but she took them off at each dry patch on the road and replaced them if there was a puddle: Waste not want not!

Mattila finds the characters credible and universal. Such hardy chattels also trod the earth in the North of England. The ingenuity of the working-class woman: Joosefiina took some old underpants and sewed up the ends to make bags for that much needed flour.

“My Finnish mother-in-law would have done the very same thing and so would my old English auntie. The similarity is amazing.”

No hard copy so far

Virginia Mattila has no plans for further Viita translations, although his anthology Betonimylläri could be a tempting proposition.

“If someone were to push it under my nose, of course I would take a look, but my thing isn’t really literature; it’s language.

Only some few individual poems from the anthology have appeared in translation.

The translation is currently only available in PDF. Numerous hopes of a hard copy have been expressed but no decision has been reached.

Virginia Mattila will be content if only she can get the front cover framed for her livingroom wall in the North of England.

“When I am dead and buried someone there may see it and say “Oh look what she must once have done. Bin it!” Sic transit gloria mundi...”

Text: Heikki Laurinolli

Earth’s Hardy Chattels is freely available on the homepages of the Lauri Viita Museum at http://www.lauriviitamuseo.fi/

Excerpts from the translation

…vaarojen, kumpujen, harjujen välitse, louhujen lomitse, oksien alitse, mökistä mökkiin ja kartanoon, lehdosta lettoon ja ojasta allikkoon – alaspäin veti kalteva kamara, etelään vietti mahtava graniittikynnös.

… over the hills and over the humps, between the ridges, through the ditches, from shack to shack and on to the manor, from spinney to swamp and from ditch to puddle – downwards drew the tilt of Earth’s crust, southward sloped the great garland of granite.

Teknillis-sosiaalinen hiidenkirnu = Infernal technological and social churn:

Järven alapäässä oli vihdoin se solmu, joka sitoi tiet ja reitit, polut ja purot yhdeksi kimpuksi. Sitä solmua ei voinut kiertää eikä avata; kerran virtaan joutuneen oli käytävä armottoman paineen läpi, joka väänsi ja vaivasi uhrinsa uuteen muotoon, ellei ilman muuta upottanut syövereihinsä jäteliejuun. Se oli teknillis-sosiaalinen hiidenkirnu, jota nimitettiin myös tehdaskaupungiksi.

At the end of the lake there came the last knot that tied routes and roads, paths and torrents into a single bundle. There was no going round it and no untying it; what was once taken up in the current was destined for the merciless mangle that knocked and kneaded its victim into a new form, unless it plunged them straight down into the sludge of its whirlpool. It was an infernal technological and social churn, and it was also called an industrial city.

The title of the translation,” Earth’s Hardy Chattels”, comes from the opening of the novel:

Maaseudulta, ei ainoastaan pohjoisesta, vaan myös lännestä, idästä, etelästä, kaikkialta virtasi jatkuvasti uutta ihmisainesta, maan sitkeätä irtaimistoa, joka unia nähden oli viimeinkin päättänyt tarttua onnensa ohjaksiin.

They came from the country, not just from the north, but from south, east and west. From all sides came the never-ending stream of human moraine, of Earth’s hardy chattels, whose dreams made them take their fate in their own hands.

Luojan palikkaleikki = The Creator’s jigsaw:

Mökin sai tehdä ihan mielensä mukaisen: pitkittäin, poikittain, vinottain; hirrestä, laudasta, paperista, sahanpurusta, tiilestä, betonista; maalata vaikka raitaiseksi; jatkaa, korottaa, tehdä jiirejä, pykäliä, portaita, siltoja, kaaveleita… Ja eikö muka tehty? Kyllä! Ei kysytty rakennuspiirustusta, ei työsuunnitelmaa, kustannusarviota, arkkitehtiä, mestaria, teettäjää – ei muuta kuin siitä poikki ja seinään. Niin kuin linnut tietävät miten pesänsä tekevät, niin syntyi Luojan palikkaleikki korkealle moreenipenkereelle.

You could build your little house just as you liked: longways, sideways or crossways. You could use logs, planks, paper, sawdust, brick or concrete. You could paint stripes on it if you wanted. You could add to the length, add to the height, you could add mitres, notches, bridges, gables... and that’s what they did. Yes, indeed! They didn’t ask you for plans or schedules, for estimates of cost, architects, masterbuilders, or who was having it built – all you had to do was cut it off there and make a wall. Just as the birds know how to build their nests, so the men of Pispala knew how the Creator’s jigsaw came together on that high embankment of gravel.