Biological age is a better indicator of your health than calendar age

Do you know how many candles would be on your cake if the number of your birthdays was based on biological age?

Biological age tells us many things that cannot be deduced from calendar age, such as general health and the risk of certain diseases and death. Biological age can differ from calendar age by up to 20 years, but the difference is usually 1–5 years.

The most significant factor affecting our biological age is genetics. Genes explain about 50% of why people of the same calendar age can have different biological ages. Moreover, the same factors that generally affect our health, such as one’s environment and lifestyle, also influence biological age.

“However, it is unclear to what extent factors like exercise, smoking, sleep, stress, nutrition, and various diseases affect biological age and to what extent these factors are independent. For example, the role of exercise has been considered important, but studies have found that the genes that make a person exercise or otherwise guide more favourable health behaviours are largely the same ones associated with lower biological age,” says Juulia Jylhävä, Leader of the Systems Biology of Aging research group at Tampere University.

With her team, Jylhävä is starting research on how air pollution and air quality affect biological age. In another study, the group will investigate how psychological and physiological stress affect biological age.

“We will also study whether individuals, who are more susceptible to stress due to their genetic makeup, are the same individuals who also have a higher biological age because of their genetic makeup. In other words, we are investigating whether stress is an independent factor,” Jylhävä says.

AI sums up biological age effects for the benefit of healthcare

About ten years ago, telomeres were a hot topic in the study of biological age. Telomeres are DNA sequences located at the ends of chromosomes whose length determines the remaining lifespan of cells. However, it was later found that epigenetic clocks rather than the length of telomeres are a decisive factor for measuring human ageing and predicting mortality. Jylhävä was involved in the research that proved this.

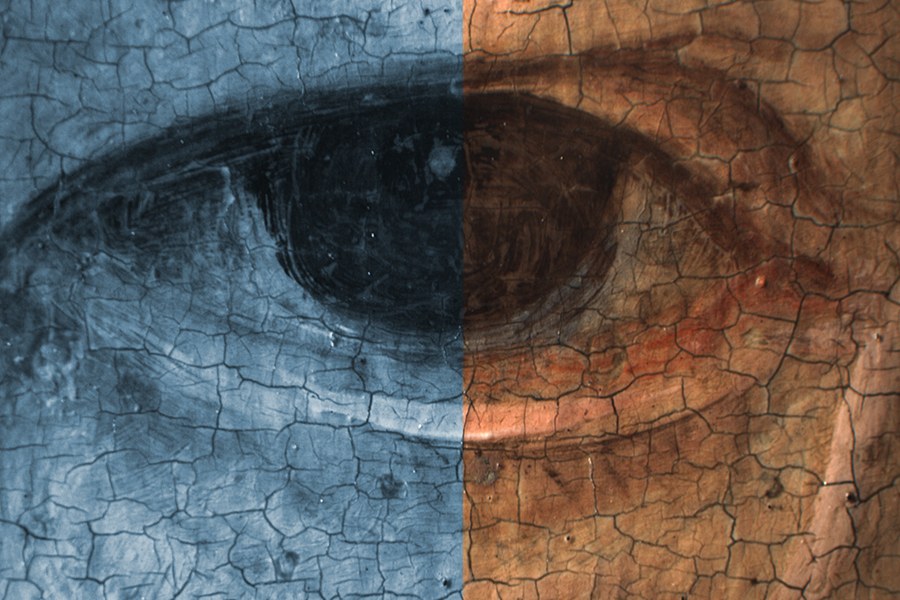

An epigenetic clock is an algorithm that measures DNA methylation patterns. Methylation is a biochemical process that continuously occurs in our cells, regulating gene expression, cell function, and differentiation. In methylation, a methyl group, a specific hydrocarbon compound, attaches to the cytosine base of DNA. The epigenetic clock considers these DNA methylation sites and calculates biological age on their basis.

While the epigenetic clock measures biological age at the cellular level, the phenomenon can also be examined at the level of the entire organism. Jylhävä’s team is currently developing an AI-based electronic frailty index for measuring frailty, the complex physiological and neurological decline associated with ageing.

For the index, Jylhävä and colleagues collect diagnoses and abnormal laboratory test results from healthcare data. The index also utilises free-text entries in electronic health records where doctors note a broad range of observations which provide additional information alongside the patient’s diagnosis.

“For example, these entries may mention whether the patient needs a cane, experiences loneliness, or finds it hard to talk due to poor hearing. This is valuable and useful information when measuring frailty,” Jylhävä points out.

The collected data are integrated into an AI model that calculates the frailty index. The index takes into account several variables related to medicine, biology, functional ability, and psychosocial factors. The higher the score, the more vulnerable the individual.

The purpose of the index is to assist healthcare in decision-making and the planning of care. The index can be used to create a health curve for the patient, which, once established, will keep updating with each healthcare visit. If the curve shows that problems are starting to accumulate, it signals the need for further check-ups or assistance. With early intervention, the patient’s care can be timed better.

“The index can also be used when the benefits and drawbacks of starting a heavy procedure are considered for patients who are older than 80 years. If the patient is very vulnerable, heavy treatments, such as those for cancer, may cause more harm than benefits. However, age matters less if the frailty index is low,” Jylhävä explains.

The index is also useful at the administrative level. It could be used, for example, to determine which healthcare units in different areas have the most vulnerable people.

“Studies show that rising healthcare costs are not so much due to the age structure but rather to the level of frailty. Thus, calendar age alone does not explain the costs, but biological age does,” Jylhävä says.

Can biological age be influenced – and is it even wise to try?

The big question is naturally whether one can influence their own biological age. When considering this, it is good to remember that biological age is not clear-cut and straightforward but consists of many factors. If one indicator is seriously in the red, it is still not a death sentence because people also have many compensatory mechanisms.

There are also ethical considerations about the extent to which it is wise to interfere with the body's processes when it is not being treated for a disease. If biological age is reduced, does the risk of illness automatically decrease as well? This is not known yet.

“When people start playing God, it does not usually lead to anything good. If we interfere with the workings of the body too much, the consequences can be unexpected,” says Jylhävä.

One of the current trends is to use existing drugs for new purposes. This interests pharmaceutical companies because developing and bringing new drugs to the market is very difficult. For example, if an existing diabetes drug also causes weight loss – and possibly rejuvenation – pharmaceutical companies strike a win.

“Especially a healthy person should carefully consider the use of drug cocktails because there are no research data on the effects of new uses of drugs yet. However, if a drug is clearly needed, such as for treating mildly elevated blood pressure or cholesterol levels, its use can also have a positive effect on biological ageing. We are also researching this in our group,” Jylhävä says.

You cannot override your genes, and it is not advisable to rush to be a guinea pig in the hopes of eternal youth, either. There is no self-help literature on proper ageing at the cellular and organism levels, and there probably never will be.

“However, nothing is stopping people from having a healthier diet and generally taking better care of themselves. Common sense will take you far. On the other hand, personalised medicine will surely gain ground in the future in the treatment of age-related medical conditions, and this is surely a welcome trend,” Jylhävä says.

Top researchers of medicine and health technology come together in November

Juulia Jylhävä will be one of the highlight speakers at MET Research Day, which will be organised on 28–29 November 2024.

Author: Sari Laapotti