Cold War association President must endure reverberations

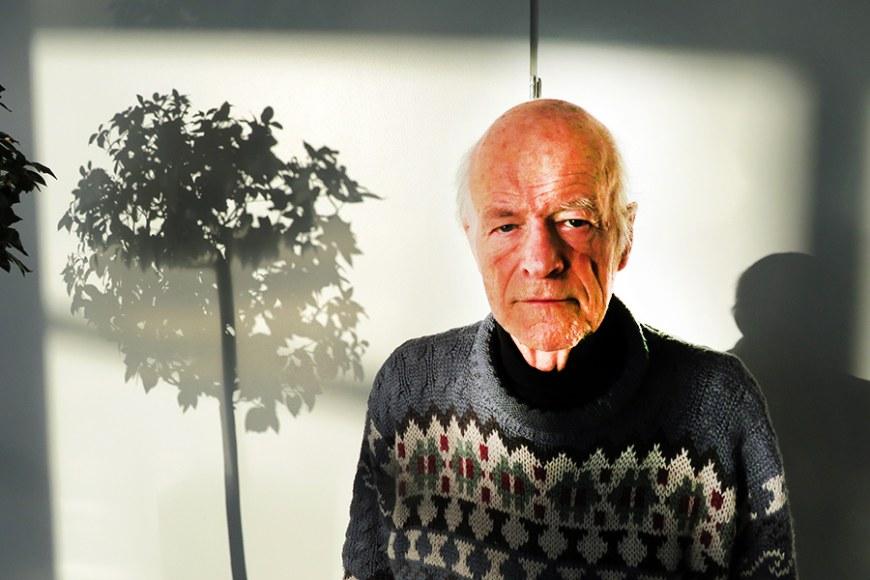

During Cold War years from 1976 to 1990, Kaarle Nordenstreng, professor emeritus of communication sciences at Tampere University, was able to exert influence, travel and meet with state leaders in his role as President of the International Organization of Journalists (IOJ).

“I do not regret my decision to accept the appointment because the post offered a lot of experience and insight,” he says even though much offensive talk and annoyance followed.

In his retirement, Nordenstreng wrote a book chronicling the entire life cycle of IOJ from 1946 to the new millennium. The book became a major endeavour on which the professor emeritus worked for almost ten years.

From ecumenicism to Cold War

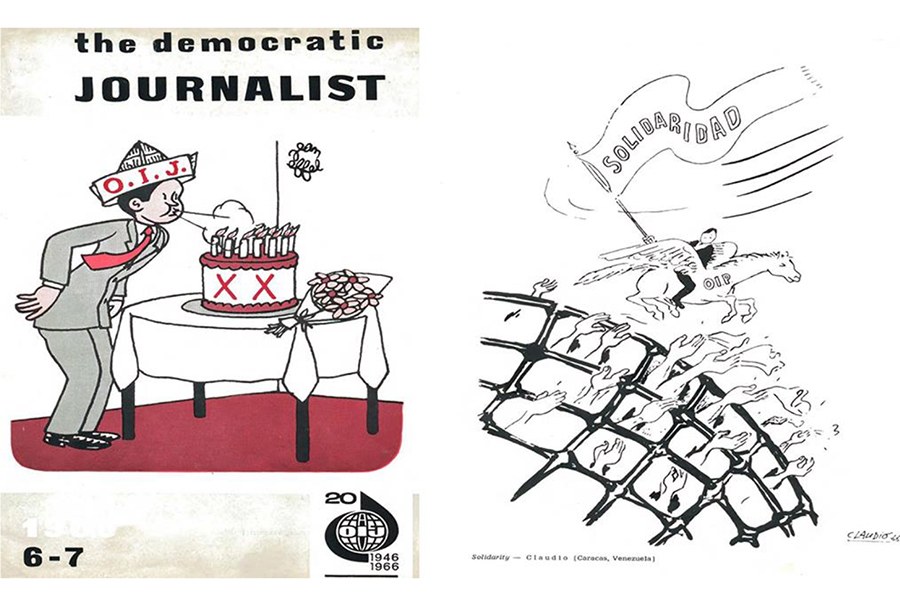

In 1946, IOJ was founded with hopeful expectations in Copenhagen.

Nordenstreng uses the word ecumenism, which has religious undertones, to describe the post-war climate of optimism that sought cooperation across ideological, geographical, and political boundaries. Only fascism, which was defeated in WWII, was left outside.

A couple of years after the IOJ was founded, a serpent slithered into the paradise of ecumenism in the form of the Cold War. Europe was divided by the Iron Curtain and many countries in Central Eastern Europe fell under the Soviet Union’s sphere of interest.

Why did the international IOJ identify with the East and the Soviet Union?

“The iceberg broke into two, and all several of these ecumenical organisations from trade unions to student unions also sided with the Eastern Bloc while the West began to set up its own counter-organisations,” Nordenstreng explains.

In addition to the Eastern Bloc countries, member organisations from only France and Finland joined the IOJ. The main Union of Journalists in Finland (SSL) sided with the Western camp while the Finnish membership in the IOJ was saved by a small union of the left-wing socialist and communist journalists (YLL).

The Soviet Union supported and Stalin was informed

According to Nordenstreng, the Soviet Union did not provide much financial assistance to the IOJ but gave it abundant indirect support.

In the Moscow State Archive of Social and Political History, he found two documents from 1949 to 1950, one of which asked Foreign Minister Molotov to support the participation of Russian journalists in the IOJ congress also financially. The second document was a letter to ‘Comrade Stalin’ marked top secret dealing with the visit of the IOJ Secretary General to Moscow.

“Of course, the letter to Stalin was political. It revealed the level on which people operated during the Cold War. In itself, the letter is insignificant in terms of the overall picture,” Nordenstreng says.

The invasion of Czechoslovakia left a trauma

Prague, the capital of Czechoslovakia and home to the headquarters of IOJ, was invaded by Warsaw Pact tanks in August 1968. The invasion left its mark, which was reflected until the Czechoslovakia’s Velvet Revolution at the end of 1989.

Should the IOJ have taken a stand against the invasion?

According to Nordenstreng, the IOJ was actually a silent supporter of the Prague Spring before the invasion. During the invasion, IOJ’s headquarters were also taken over and the organisation conflicted with the soldiers.

“When the situation stabilised, IOJ was allowed to remain operational, but it did not make much noise of what had happened,” he says.

After the Velvet Revolution, it became clear that journalists forced to go underground during the invasion had been left with a great deal of resentment towards the IOJ.

“In 1968, a couple of thousand journalists lost their jobs and were employed as street sweepers and in other menial jobs, which had also happened to the intelligentsia in general in Czechoslovakia after 1948. On both occasions, the IOJ did not make a big deal about its members being ousted and it sort of turned a blind eye to those developments. With hindsight one may consider whether the IOJ was too favourable to the new rulers or whether that was necessary realism,” Nordenstreng points out.

However, he says that most Czechoslovakian journalists kept their jobs after the invasion in 1968.

“They swallowed their pride and did not start criticising the new administration but operated within that framework,” he says.

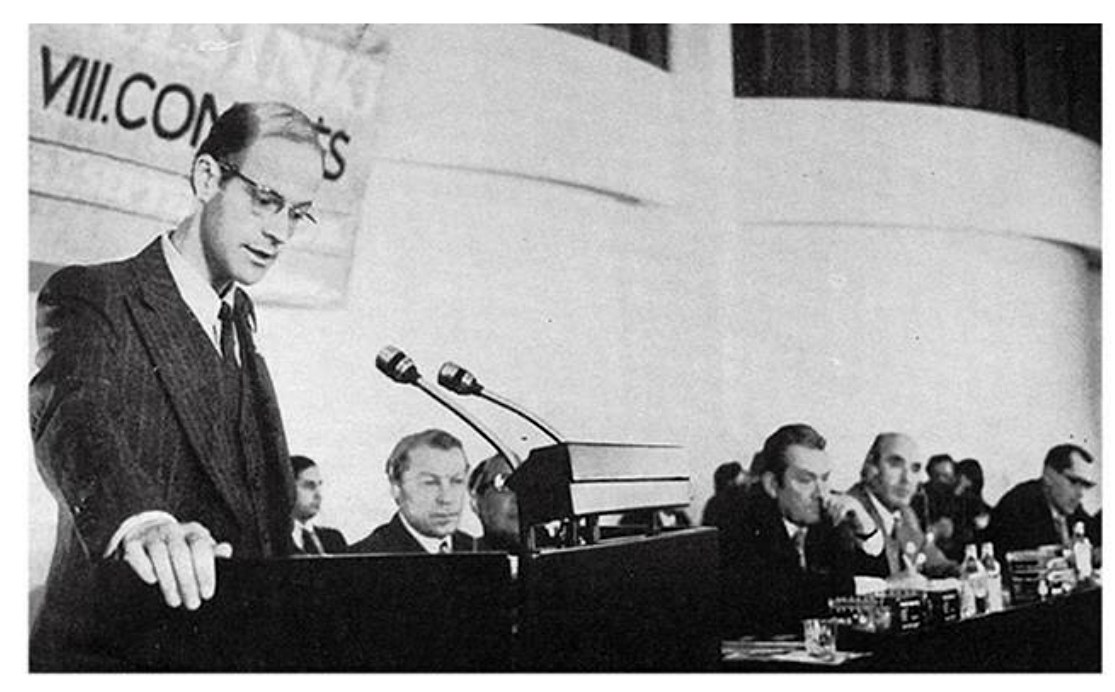

Becoming President with support from the Soviet Union

In 1976, Nordenstreng was elected President of the IOJ at the age of 35 on a proposal by the Soviet Union. This coincided with an era when universal leftism and détente were on the rise in the spirit of the CSCE.

“The key was détente and CSCE, not so much leftism. What was crucial was that I was not a member of any party, especially not the Communist Party. That would have been a burden in the organisation. For the Soviet Union at that time, a progressive non-partisan such as myself was the best brand available,” he says.

Did some people bear a grudge because the appointment was dictated by an outsider?

“Yes. In particular, the chairman of YLL in Finland was very upset and felt that a university professor should not sideline long-standing union heroes in the post,” Nordenstreng says.

However, good relations with YLL were restored quite soon. Nordenstreng saw his appointment as a positive recognition, which made him a marked man regardless.

His former boss at the University of Tampere, Aamulehti newspaper’s editor-in-chief Raimo Vehmas, greeted Nordenstreng at a cocktail party in Russian: “How do you do, comrade!”

“It conveyed the message that I had been branded,” Nordenstreng says.

He hesitated to take over the presidency for work reasons because it required much travel and took time from his work as professor. The presidency was not a main job, but a position of trust he held alongside his professorship.

“I had a certain kind of drive to reform the organisation. I thought the IOJ was stagnant or a little old-fashioned. It did follow up on détente as the Helsinki congress showed, but the professional side was quite undeveloped. The organisation was more political than professional. My intention was to strengthen the professional side and return the IOJ back to its ecumenical roots. That was my real challenge,” Nordenstreng says.

Not invited to become a spy and no feasting with Home Russians

There are many detective stories about spies and the movements of undeclared money in the time of the Cold War, but Nordenstreng did not encounter such things.

The leaders of the Finnish People’s Democratic League warned the new IOJ President that he will face tough situations when approached by the CIA and the KGB.

“However, they did not come for me. That went surprisingly well. Six months after my appointment, I became a visiting professor at a leading research university in San Diego, United States. I imagined that I would be subjected to some sort of harassment or attempts to lure me here or there, but the whole intelligence world remained surprisingly distant,” Nordenstreng says.

Former President of Finland Urho Kekkonen has also been alleged to be a Soviet agent, so why not you?

“Kekkonen was not an agent but used the KGB to implement his political ideas. I didn’t even have any of the so-called Home Russians. I was quite openly involved with the leadership of the Journalists’ Union of the Soviet Union, the largest member organisation of the IOJ. Of course, that organisation represented the official policy of the Soviet Union and the tentacles of the KGB, but I had no direct dealings with them,” Nordenstreng points out.

He kept in close touch with Viktor Afanasyev, the editor-in-chief of the Pravda newspaper and leader of the member organisation of IOJ in the Soviet Union.

“I constantly reported to him on what was happening in the IOJ and, as it were, took from him my mandate to develop the organisation in a more professional and less old-fashioned political direction. Back then, there was a kind of pre-Gorbachev thaw, which I took advantage of. I played my hand a bit like Kekkonen,” Nordenstreng explains.

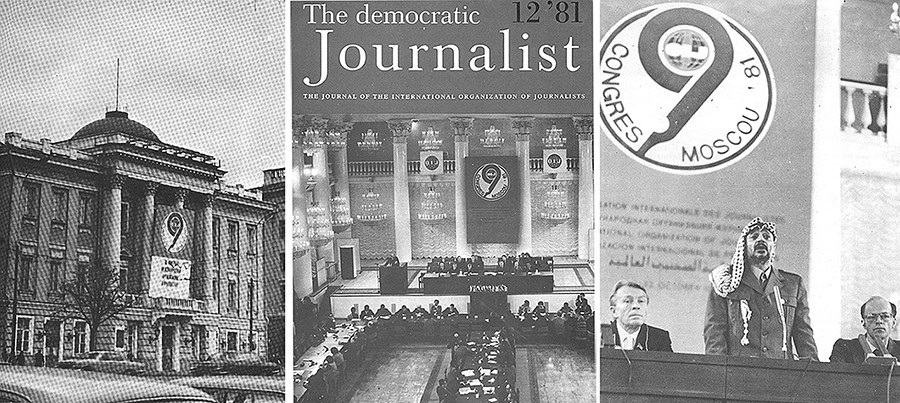

By the 1980s, the IOJ had grown into the world’s largest media organisation with its own schools of journalism, a publishing house, and an interpreter service. The organisation’s funding was mainly based on commercial companies in Prague and Budapest. They had a politically protected exclusive status, which critics call “islands of capitalism in the sea of socialism”.

Criticism grew in the 1990s

In 1990, when the communist regimes collapsed and Eastern Europe was liberated, Nordenstreng and his organisation began to be criticised. Usual insults included ‘puppet’ and ‘useful idiot’.

According to Nordenstreng, these monikers were intended to downplay his actions and place him as a middleman in a greater quest for power.

“To this I can only say yes, of course, when you start doing something like this, you must endure everything that comes with it. The question is whether one’s endeavours accomplish something. I claim that I succeeded up to a point in what I was trying to do to make the IOJ more professional and ecumenical,” he explains.

Nordenstreng says that he was not alone in his efforts. A wide circle of supporters, especially Finns, were involved.

“The entire SSL was behind the efforts at that point. I frequently consulted with them and had a large reference group led by the Chair of the union. I was by no means a one-man show but an actor representing certain aspirations,” he says.

In the 1980s, the SSL became an associate member of the IOJ, which, according to Nordenstreng, was much more involved than many full members.

“The Union of Journalists in Finland played a very important role in the activities of the IOJ, partly through me and partly in spite of me,” he says.

IOJ ran out of steam

In the 1990s, following the break-up of the Eastern Bloc, the IOJ’s operating conditions narrowed and the organisation was expelled from Czechoslovakia. A small firm was allowed to stay in Prague on the condition that its political and professional activities cease.

According to Nordenstreng, the IOJ’s empire did not really collapse but ran out of steam from within.

“I tried my best to make that big and collapsed balloon into something that could build on its ecumenical roots from 1946,” he says.

IOJ’s cooperation with the Western sister organisation International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) was not successful.

“There was an atmosphere of post-Cold War bravado. The IFJ’s leadership lacked wisdom and foresight. They said they had won the Cold War and wanted to bin the IOJ. Had they been wise, they would have realised that the IOJ had financial resources which could have been shared with a wider circle,” Nordenstreng says.

He regrets that assembling a large trade union free of old political contradictions did not happen.

The merger took place in a different manner with the former IOJ member organisations joining the Western IFJ, where, according to Nordenstreng, they placed on the lower rungs.

In 1996, he participated in the IFJ’s congress where the demise of IOJ was declared.

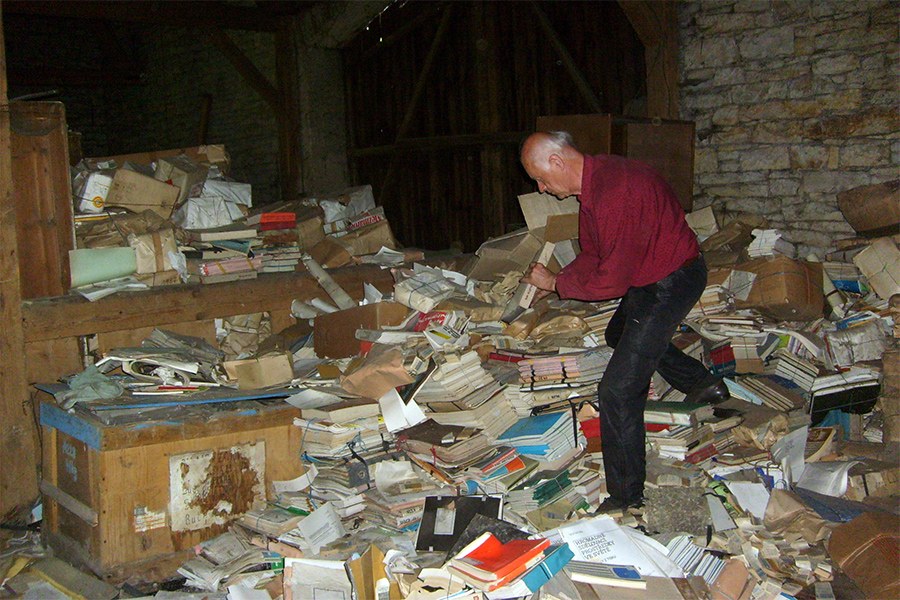

The IOJ history book was published by Karolinum, the Charles University Press in Prague. In addition to Nordenstreng’s more than 200-page history, the book contains over a hundred pages of memoirs from journalists involved in the IOJ and nearly 200 pages of previously unpublished documents.

Text: Heikki Laurinolli

Kaarle Nordenstreng: The Rise and Fall of the International Organization of Journalists Based in Czechoslovakia 1946–2016. Charles University Press, Prague 2020.